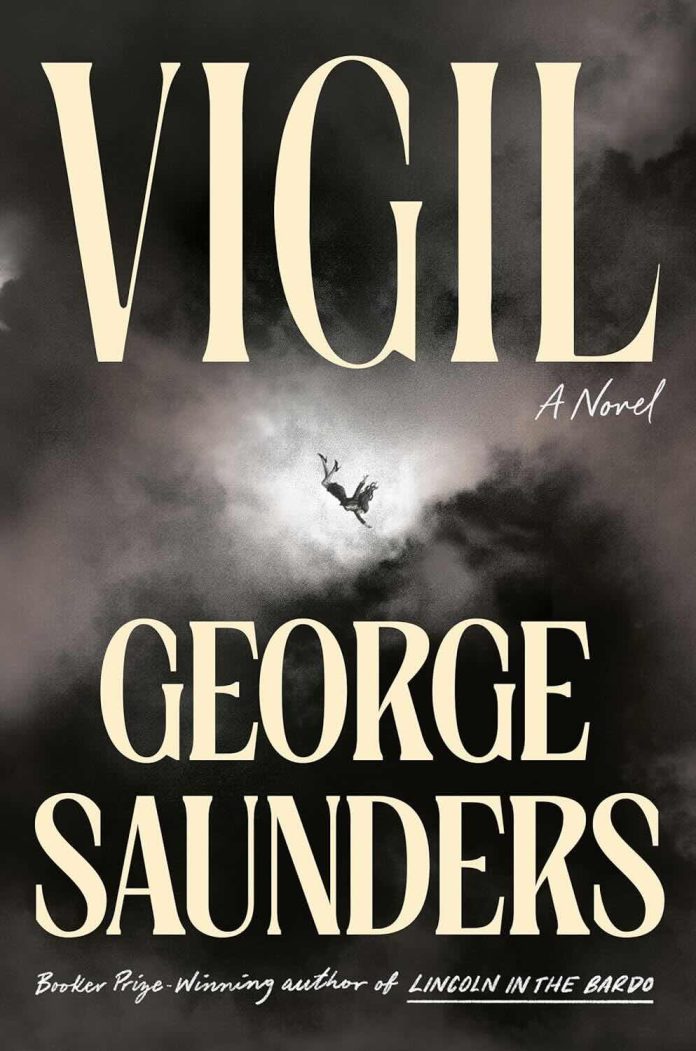

George Saunders returns with his most ambitious and urgent work yet, a metaphysical meditation on accountability that burns with the quiet fury of a planet on fire. Vigil by George Saunders takes readers on a phantasmagorical deathbed journey that feels equal parts Dickensian morality tale and contemporary climate reckoning, wrapped in the author’s signature blend of comic absurdism and devastating empathy.

A Premise Both Ancient and Startlingly Modern

The novel opens with our narrator, Jill “Doll” Blaine, plummeting toward Earth—not for the first time. Since her accidental death in 1976 Indiana (a car bombing meant for her police officer husband), Jill has served as a psychopomp, a spiritual guide tasked with comforting the dying in their final moments. She’s performed this sacred duty 343 times, and it’s become almost routine. Almost. Her latest charge, however, proves exceptional in the worst possible way: K.J. Boone, an oil company CEO lying in his Dallas mansion, refuses to acknowledge a single regret as his organs systematically fail.

What follows is a compressed epic—one night that spans decades of memory, encompasses global catastrophe, and questions whether redemption remains possible when the consequences of one’s actions threaten the entire planet. Vigil by George Saunders transforms a single bedroom into a cosmic courtroom where the prosecution arrives in waves: endangered birds manifesting by the hundreds, a guilt-ridden French engineer who invented the combustion engine, colleagues from Boone’s past, and perhaps most devastatingly, Mr. Bhuti, a lawyer from drought-ravaged India who died alongside his wife and mother when their village became uninhabitable.

The Stubborn Complexity of Jill Blaine

Saunders has always excelled at creating narrators who are simultaneously ordinary and extraordinary, and Jill ranks among his finest creations. She exists in a perpetual state of becoming—neither fully the Indiana waitress who loved her husband Lloyd nor completely the “elevated” spiritual being she’s meant to be. Her struggle with what she calls “elevation” (a Buddhist-inflected detachment from ego and earthly concerns) provides the novel’s emotional spine.

The author brilliantly renders Jill’s consciousness through shifting linguistic registers. When she maintains her elevated state, her diction becomes formal, almost archaic: “I cherished my task,” “I could comfort.” But memories of her former life—marked by quotation marks around objects and experiences (“Chevelle,” “Slurpee cup,” “bicentennial summer”)—pull her back toward the particular and personal. This typographical innovation isn’t mere stylistic flourish; it visualizes the very tension at the novel’s heart: how do we balance universal compassion with personal grief? How do we maintain perspective when our own story still aches?

Jill’s journey to Stanley, Indiana, roughly two-thirds through the novel, represents both the book’s emotional climax and its most risky narrative gambit. Here, Saunders tests our patience as Jill indulges in increasingly detailed reminiscences of Lloyd, “Jardine’s Smorgasbord,” and the life she lost. Some readers may find this extended digression frustrating, but it’s essential to understanding Jill’s ultimate choice and the novel’s complex position on forgiveness.

The Paradox of K.J. Boone

K.J. Boone could have been a simplistic villain—the greedy oil executive deserving our contempt. Instead, Saunders performs his characteristic act of radical empathy, showing us Boone’s Wyoming poverty, his father’s cruelty, his genuine love for his wife and daughter. We understand exactly how this “short little Wyoming hick” became the bantam rooster who ruthlessly climbed to CEO, who convinced himself that questioning climate science was merely “having a hypothesis,” who funded misleading studies while privately redesigning oil rigs to accommodate rising seas.

The novelist’s greatest achievement here is making Boone’s rationalizations feel devastatingly human rather than monstrous. When Boone protests that he’s “inevitable”—that he couldn’t have been anyone other than who he was—he’s invoking the very philosophy Jill has been taught to embrace. This creates an ethical knot the book never fully unties, and perhaps shouldn’t. If we’re all inevitable products of our circumstances, shaped by forces beyond our control, where does accountability begin?

A Carnival of Consequences

Vigil by George Saunders achieves its most startling effects through surrealist set pieces that somehow feel more real than realism could manage. When the Frenchman (the engineer who invented the combustion engine) brings endangered bird species to confront Boone, the scene operates on multiple levels simultaneously: comic farce (Boone’s irritation at the spectacle), ecological horror (each species’ particular doom catalogued), and metaphysical terror (the weight of extinction made manifest).

Similarly, the arrival of “the Mels”—two deceased scientists who helped Boone spread climate misinformation—provides both dark comedy and genuine chill. They reproduce asexually, miniature versions plopping out of their rears and growing to full size, literalizing how bad ideas propagate. Their plan to claim Boone’s spirit and roam the earth encouraging other dying executives feels like something from a Hieronymus Bosch painting reimagined for the Anthropocene.

Where the Novel Soars and Stumbles

Saunders’s prose remains among the finest in contemporary American fiction—capable of achieving maximum effect with minimal means. His ability to modulate between registers (Jill’s formal elevation-speak, Boone’s Wyoming-inflected corporate-ese, the Frenchman’s accented English) creates a linguistic texture that mirrors the novel’s thematic concerns about identity and transformation.

The book’s philosophical ambitions, however, occasionally overwhelm its dramatic ones. The concept of “elevation”—essentially Buddhist non-attachment presented as spiritual advancement—gets explained and re-explained until the metaphysical machinery starts showing. We understand what elevation means intellectually long before the plot requires us to, creating moments where the novel feels more like a thesis than a story.

Additionally, Vigil by George Saunders doesn’t quite reach the heights of Lincoln in the Bardo. That earlier novel’s polyphonic chorus of voices created genuine emotional devastation; here, the narrower focus on Jill and Boone sometimes feels claustrophobic despite the cosmic scope. The ending, in which Jill intervenes to save Boone and send him off with the Frenchman to convert other dying oil executives, strains credulity even by the novel’s own magical realist rules. It feels more like wish fulfillment than earned resolution.

The pacing also proves uneven. The Indiana digression, while thematically important, disrupts narrative momentum at a crucial moment. And some readers may find the wedding next door—where Jill keeps escaping to observe the living—more tedious than illuminating on subsequent visits.

A Lineage of Moral Imagination

Readers familiar with Saunders’s work will recognize Vigil by George Saunders as both evolution and continuation. The surrealist corporate hellscapes of CivilWarLand in Bad Decline and Pastoralia find new expression here, while the historical and moral scope recalls Lincoln in the Bardo‘s engagement with American sin. The precision of the stories in Tenth of December and Liberation Day manifests in individual set pieces, even if the novel’s overall structure feels looser.

The book exists in conversation with other climate-conscious literature—Omar El Akkad’s American War, Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, Richard Powers’s The Overstory—but Saunders’s metaphysical approach offers something distinct. Where those novels ground climate catastrophe in realist narrative, Vigil by George Saunders uses fantasy to make the moral stakes feel immediate and personal.

Books That Resonate in Similar Registers

Readers moved by this novel might explore:

- Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders – For comparable metaphysical ambition and historical reckoning

- The Hearing Trumpet by Leonora Carrington – For surrealist spiritual quest narratives

- Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell – For interconnected stories exploring consequence across time

- The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson – For climate fiction tackling systemic change

- White Noise by Don DeLillo – For darkly comic engagement with American death and denial

The Uncomfortable Questions That Linger

What makes Vigil by George Saunders essential reading despite its flaws is its willingness to sit with moral complexity rather than resolve it neatly. The novel asks whether understanding someone fully means forgiving them completely—and doesn’t provide easy answers. It questions whether the dying moment offers genuine opportunity for transformation or merely illusion. Most urgently, it wonders whether individual redemption matters when collective damage proves irreversible.

Saunders has crafted a profoundly uncomfortable book for our profoundly uncomfortable moment. It refuses to offer the consolation its protagonist seeks or the straightforward moral clarity readers might crave. Instead, it insists we sit vigil ourselves—bearing witness to how we got here, who benefits from our collective denial, and what it might cost to finally see clearly. In an era of climate catastrophe and corporate malfeasance, such clear-eyed reckoning feels both necessary and insufficient, which may be precisely the point.