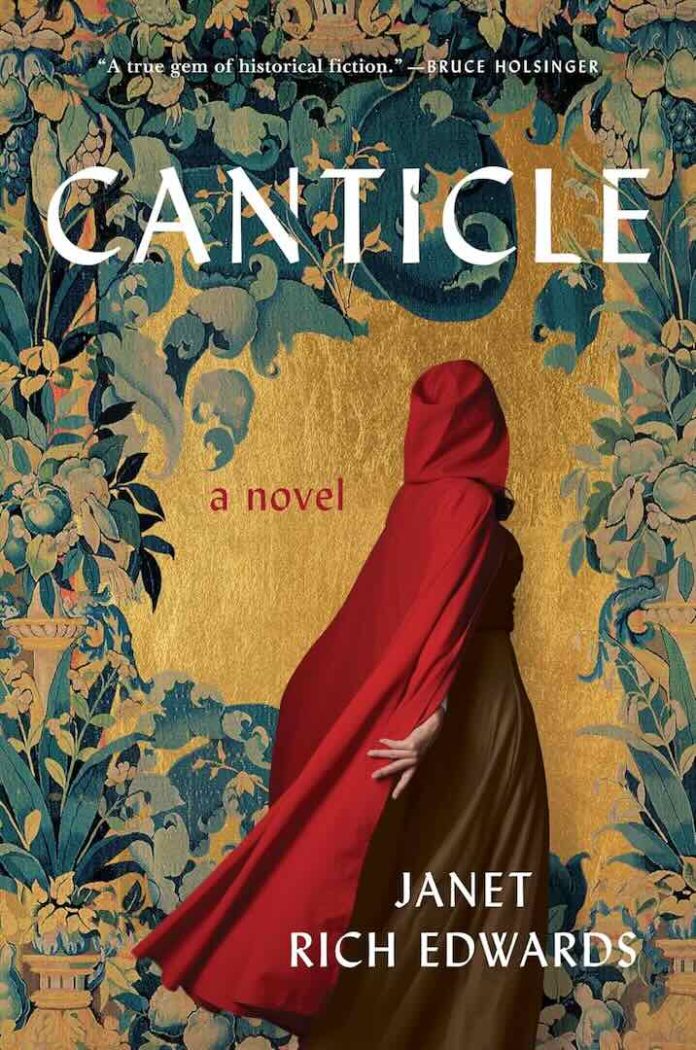

Janet Rich Edwards delivers a stunning debut with Canticle, a historical novel that weaves the intimate struggles of a young mystic with the political machinations of thirteenth-century Bruges. This is not your typical medieval tale of religious devotion—it’s a searching examination of what happens when personal revelation collides with institutional power, when women dare to seek God on their own terms, and when the line between spiritual ecstasy and dangerous heresy becomes perilously thin.

The Architecture of Belief

Set against the backdrop of 1299 Bruges, Edwards constructs a world where wool merchants and bishops jostle for power, where women form their own communities outside Church control, and where the act of translating scripture into the vernacular becomes a revolutionary—and potentially fatal—act. The novel centers on Aleys, a sixteen-year-old whose mystical visions set her on a collision course with the religious establishment.

What makes this debut particularly impressive is Edwards’s refusal to romanticize the medieval period or her protagonist’s spiritual journey. Aleys is no plaster saint; she’s stubborn, occasionally arrogant, and deeply uncertain. Her path from reluctant runaway bride to Franciscan novice to miracle-working anchoress unfolds with psychological complexity that feels utterly contemporary while remaining rooted in the medieval worldview. Edwards captures the vertigo of religious doubt alongside the intoxication of spiritual certainty, showing us a young woman who craves divine union but cannot always distinguish God’s voice from her own desires—or worse, from manipulation.

The Beguines emerge as the novel’s most compelling creation. These historically real communities of independent religious women who refused both marriage and the cloister offer Aleys a glimpse of female solidarity and intellectual freedom. Through characters like Sophia, the wise magistra; Katrijn, the skilled draper with a sharp tongue; and Ida, whose gentle presence grounds the community, Edwards brings to life a forgotten model of women’s spiritual and economic autonomy. Their hospital work, their carding of wool, their secret study of Latin scripture—all of it feels meticulously researched yet never pedantic.

Prose That Prays and Bleeds

Edwards writes with a distinctive voice that echoes medieval mystical literature while remaining accessible to modern readers. Her prose can shift from the spare beauty of monastic simplicity to lush sensory detail, mirroring Aleys’s oscillation between spiritual clarity and earthly confusion. The descriptions of Aleys’s visions—God as ocean wave, as mountain and tide, as light dissolving her very substance—carry genuine power without tipping into New Age pastiche.

Consider this passage describing the Beguines’ chapel service: the call-and-response singing of the Song of Songs, voices weaving together like a nest being built, the realization that “they all yearn as she does.” Edwards understands that medieval spirituality was communal, embodied, and often ecstatic in ways we’ve forgotten. She gives us a Christianity that dances and weeps, that finds God in market squares and deathbeds, not just in cathedrals.

The novel’s structure deserves particular praise. Edwards divides the narrative into four books with chapters alternating between Aleys and the men who seek to control her: Friar Lukas, her spiritual director whose devotion curdles into obsession; and Bishop Jan, her spiritual director’s brother, a cynical politician who sees sainthood as a business opportunity. This multiperspective approach allows Edwards to expose the machinery of power behind religious authority while maintaining empathy for even her most flawed characters.

The Shadows in the Light

Yet Canticle by Janet Rich Edwards is not without its rough edges, which may account for its solid but not exceptional reception among early readers. The pacing occasionally stumbles, particularly in the middle section where Aleys performs miracles in the hospital. Edwards lingers perhaps too long on the uncertainty of Aleys’s healing gift—we understand her doubt after the first few failures, but the repetitive cycle of faith and doubt can feel like treading water.

More problematic is the character of Friar Lukas, whose descent from sincere spiritual mentor to something far darker feels rushed and insufficiently developed. His transformation needed more psychological scaffolding to be fully convincing, though Edwards deserves credit for refusing to make her male religious figures simple villains. Even Bishop Jan, calculating and worldly, receives moments of complexity that elevate him beyond stereotype.

The novel’s treatment of Aleys’s miraculous healings walks a deliberate tightrope—are they real? psychosomatic? coincidental? Edwards never fully commits to an answer, which some readers may find frustrating. This ambiguity serves the novel’s larger themes about the unknowability of divine will, but it can leave the narrative feeling oddly suspended between the mystical and the mundane.

The ending, which I won’t spoil, opts for a kind of transcendent ambiguity that may not satisfy readers seeking either clear martyrdom or miraculous salvation. It’s a bold choice that honors the novel’s refusal of easy answers, though it risks leaving the emotional arc feeling incomplete.

What History Illuminates

Beyond its narrative strengths, Canticle by Janet Rich Edwards succeeds as a work of historical recovery. Edwards draws on the writings of actual medieval mystics—Meister Eckhart, Julian of Norwich, Catherine of Genoa—and the documented history of Beguine communities to craft a world that feels both foreign and startlingly relevant. The novel asks: What happens when women claim direct access to God? Who gets to control spiritual truth? At what point does personal revelation become heresy?

These questions resonate powerfully in our current moment of religious and political polarization. Edwards doesn’t draw heavy-handed parallels to contemporary debates about women’s authority or institutional versus personal faith, but they’re there for readers who want to find them. The novel’s exploration of how translation—literally making scripture accessible in common language—becomes an act of rebellion speaks to ongoing arguments about who owns sacred texts and how they should be interpreted.

The historical detail enriches rather than encumbers the narrative. Edwards clearly did her research on medieval Bruges’s wool trade, hospital practices, religious orders, and the Beguine communities, but she wears her learning lightly. We get enough sensory texture—the smell of fleece, the taste of barley gruel, the amber light through horn windowpanes—to feel transported without getting mired in historical exposition.

Why This Matters

Edwards has given us a medieval historical novel that thinks deeply about faith without being devotional, that centers women without being ahistorical, and that grapples with institutional power without being reductive. It’s a book that trusts its readers to sit with uncertainty, to find beauty in questions rather than answers.

For readers who appreciated the intellectual rigor of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy, the spiritual seeking of Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, or the medieval women’s stories in Geraldine Brooks’s Year of Wonders, Canticle offers rich rewards. It joins recent works exploring women’s spiritual authority in restrictive religious contexts, though Edwards’s medieval setting allows her to examine these tensions at their historical root.

This is a novel that demands—and deserves—careful reading. Edwards’s prose can be dense, her spiritual discussions complex, her refusal to moralize occasionally frustrating. But for readers willing to enter Aleys’s claustrophobic cell, to breathe the incense and doubt alongside her, Canticle by Janet Rich Edwards offers an experience both intellectually challenging and emotionally resonant.

For Readers Who Loved

If Canticle by Janet Rich Edwards resonates with you, consider these similar journeys into women’s spiritual lives and medieval mysteries:

- The Book of Margery Kempe by Robert Glück—A contemporary reimagining of the medieval mystic’s autobiography

- Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell—Though set in Elizabethan England, shares Edwards’s gift for psychological interiority within historical constraint

- The Physician’s Daughter by Martha Ockley—Another examination of women’s knowledge and power in medieval Europe

- Girl with a Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier—For Edwards’s attention to sensory detail and women’s circumscribed choices

- Silence by Shūsaku Endō—A profound meditation on faith under persecution that matches Canticle‘s spiritual seriousness

The Final Word

Canticle announces Janet Rich Edwards as a writer to watch. While not flawless, her debut demonstrates remarkable ambition and an distinctive voice. She’s crafted a novel that takes women’s spiritual yearning seriously, that refuses to sentimentalize the past, and that finds in a thirteenth-century begijnhof questions that still haunt us today. For readers seeking historical fiction with intellectual depth and spiritual weight, Canticle offers a rare and valuable gift: a story that illuminates both medieval faith and our contemporary longings for meaning, community, and transcendence.