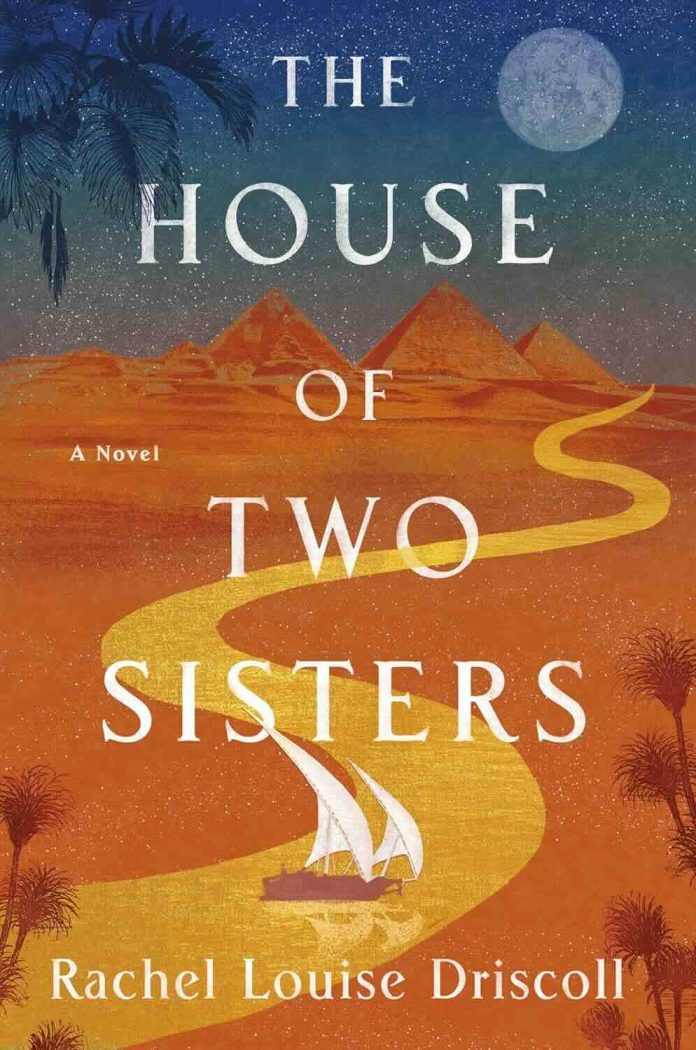

Rachel Louise Driscoll’s debut novel The House of Two Sisters stands as a remarkable achievement in historical gothic fiction, weaving together the Victorian fascination with Egyptology, the intimate bonds of sisterhood, and the dark consequences of cultural pillaging. This atmospheric tale follows Clementine Attridge as she navigates both the treacherous waters of the Nile and the equally dangerous currents of family curses, colonial exploitation, and murderous betrayal.

The Layered Architecture of Myth and Reality

Narrative Structure and Storytelling Technique

Driscoll employs a masterful dual-timeline structure, alternating between the present action in Egypt (1892) and haunting flashbacks to Essex (1887-1891). The novel’s chapters are punctuated by “Unwrapping” sections that gradually reveal the truth like layers of mummy bandages being peeled away. This technique mirrors the archaeological excavations at the story’s heart while creating mounting suspense that keeps readers turning pages well into the night.

The author’s background as a former librarian shines through in her meticulous research and authentic period details. From the bustling bazaars of Cairo to the genteel drawing rooms of Essex, every setting feels lived-in and historically accurate. Driscoll’s prose captures the Victorian voice beautifully, with Clemmie’s narration bearing the formal cadence of the era while maintaining emotional immediacy.

Character Development and Psychological Depth

Clementine “Clemmie” Attridge emerges as a complex protagonist who defies Victorian stereotypes. As a skilled hieroglyphist in a male-dominated field, she represents the New Woman while still being constrained by societal expectations. Her relationship with her sister Rosetta forms the emotional core of the novel, and Driscoll excels at depicting how childhood games of make-believe can cast long shadows into adulthood.

The supporting cast proves equally well-developed. Mariam, the dahabeeyah captain’s daughter, provides a crucial Egyptian perspective on the cultural theft perpetrated by Western collectors. Her gentle guidance toward repatriation represents a moral compass in a world of exploitation. Rowland Luscombe serves as both romantic interest and moral gray area—his betrayal of Clemmie’s trust by stealing the amulet adds layers of complexity to their relationship.

Horatio Devereux stands as a genuinely menacing antagonist whose charming facade conceals murderous ambition. His transformation from protective family friend to calculating killer provides the novel’s most chilling character arc.

Thematic Richness and Cultural Commentary

The Ethics of Archaeological Collection

One of the novel’s greatest strengths lies in its unflinching examination of Victorian-era antiquities collecting. Through Clemmie’s growing awareness of her father’s complicity in illegal excavation and trafficking, Driscoll explores themes that remain painfully relevant today. The mummified twins at the story’s center become symbols of cultural violation—ancient sisters torn apart by Western greed, just as Clemmie and Rosetta are separated by the consequences of their father’s actions.

Mariam’s biblical reference to Joseph’s bones provides a powerful argument for repatriation: “Our bones don’t belong in a foreign place, ya aanesa Clemmie. They should be buried in their home country.” This sentiment cuts to the heart of ongoing debates about museum collections and cultural heritage.

Sisterhood Across Boundaries

The novel’s exploration of sisterhood operates on multiple levels. The mythological sisters Isis and Nephthys provide the framework for understanding Clemmie and Rosetta’s relationship, while the friendship between Clemmie, Celia, and Mariam demonstrates how sisterhood can transcend cultural and class boundaries. The recurring motif of kites (birds sacred to Isis and Nephthys) serves as a visual reminder of these connections throughout the narrative.

Gender and Agency in Victorian Society

Driscoll skillfully depicts the limitations placed on Victorian women while celebrating their resilience and ingenuity. Clemmie’s expertise in hieroglyphics gives her unusual agency, yet she still faces dismissal from male colleagues and pressure to marry. Her journey to Egypt represents both literal and metaphorical liberation, though the cost proves steep.

Atmospheric Excellence and Gothic Elements

Sense of Place and Mood

The novel’s atmospheric writing transports readers effortlessly from the fog-shrouded estates of Essex to the sun-baked monuments of Egypt. Driscoll’s descriptions of the Nile journey capture both the romance and danger of Victorian travel, while her depiction of mummy unwrapping parties perfectly balances fascination with revulsion.

The recurring imagery of unwrapping—both literal and metaphorical—creates a sense of gradual revelation that builds toward the dramatic confrontations at Philae. The author’s use of Egyptian mythology as both backdrop and psychological framework adds depth to what could have been simple adventure fiction.

Supernatural Elements and Ambiguity

Perhaps the novel’s most impressive achievement is its treatment of the supernatural. Are the family’s misfortunes truly the result of an ancient curse, or merely the consequences of Horatio’s greed and violence? Driscoll maintains this ambiguity masterfully, allowing readers to interpret events through either lens while never definitively resolving the question.

The asthma attacks, kite sightings, and dust storms that plague Clemmie could be symptoms of guilt and anxiety—or manifestations of Nephthys’s displeasure. This psychological complexity elevates the novel above simple gothic melodrama.

Technical Craft and Literary Merit

Prose Style and Voice

Driscoll demonstrates impressive command of Victorian prose without falling into pastiche. Her sentences carry appropriate formality while maintaining modern readability. The dialogue feels authentic to the period, and she handles multiple accents and dialects with sensitivity, particularly in Mariam’s speech patterns.

The author’s imagery proves consistently evocative, from the “platinum snake” of the River Chelmer to the “blood-sodden nightdress” of the climactic confrontation. These details create vivid mental pictures while reinforcing thematic elements.

Research and Historical Accuracy

The novel’s historical research appears impeccable, from details about Egyptian excavation methods to the specifics of Victorian mourning customs. Driscoll’s author’s note reveals extensive consultation of primary sources, and this scholarship shows in the authentic period atmosphere.

The depiction of colonial Egypt feels particularly well-researched, acknowledging both the period’s fascination with “exotic” cultures and the destructive impact of Western collecting practices.

Areas for Critical Consideration

Pacing and Structure

While the dual timeline creates effective suspense, some readers may find the numerous flashbacks occasionally disruptive to narrative momentum. The “Unwrapping” sections, while thematically appropriate, sometimes break up action sequences at inopportune moments.

Resolution and Ambiguity

The novel’s ambiguous ending regarding the curse’s reality may frustrate readers seeking definitive answers. While this ambiguity serves the story’s themes, some plot threads feel slightly underresolved, particularly regarding the fate of the twins’ remains.

Character Motivations

Horatio’s transformation from protective friend to cold-blooded killer, while effectively shocking, could benefit from deeper psychological exploration. His motivations, while clear, feel somewhat surface-level compared to the rich inner lives of other characters.

Literary Connections and Influences

The House of Two Sisters draws clear inspiration from Victorian sensation novels while maintaining distinctly modern sensibilities. Readers will find echoes of:

- Wilkie Collins’ intricate plotting and multiple perspectives

- Sarah Waters’ atmospheric historical fiction and complex female relationships

- Elizabeth Peters’ Amelia Peabody series in its Egyptian setting and archaeological mysteries

- Tana French’ psychological complexity and unreliable narration

The novel also shares DNA with classic gothic works like Bram Stoker’s The Jewel of Seven Stars in its treatment of Egyptian supernatural elements, while approaching cultural appropriation with modern awareness that earlier works lacked.

Conclusion: A Promising Debut with Lasting Impact

The House of Two Sisters announces Rachel Louise Driscoll as a significant new voice in historical fiction. While the novel has minor structural weaknesses, its atmospheric power, complex characters, and relevant themes more than compensate for these concerns. The book succeeds both as entertainment and as serious engagement with issues of cultural heritage, colonial exploitation, and female agency.

Driscoll’s decision to center the story around sisterhood—both mythological and literal—provides emotional resonance that elevates the adventure plot into something more meaningful. The novel’s exploration of how childhood games can shape adult reality feels particularly poignant, while its treatment of archaeological ethics remains sadly timely.

For readers who appreciate richly atmospheric historical fiction with gothic elements, complex female protagonists, and thoughtful engagement with colonial history, The House of Two Sisters delivers on all counts. It stands as both an engaging debut and a promising indication of the author’s potential for future works.

The novel’s ultimate message—that some things should never be taken from their homeland, whether ancient artifacts or human remains—resonates powerfully in our current moment of reckoning with museum collections and cultural repatriation. In this way, Driscoll has crafted not just an entertaining historical novel, but a relevant contribution to ongoing cultural conversations.

Similar Books You Might Enjoy

If you enjoyed The House of Two Sisters, consider these similar reads:

- The Egyptologist by Arthur Phillips – A darkly comic take on Egyptian archaeology and obsession

- The Book of Lost Names by Kristin Harmel – Another novel about preserving cultural heritage under threat

- Enlightenment by Sarah Perry – Victorian gothic atmosphere with scientific skepticism

- The Invisible Bridge by Julie Orringer – Historical fiction exploring how past traumas echo through generations

- The Ten Thousand Doors of January by Alix E. Harrow – Portal fantasy with themes of cultural preservation

- Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia – Gothic atmosphere with ambiguous supernatural elements

Rachel Louise Driscoll has crafted a debut that honors both the entertainment value of historical gothic fiction and the serious themes underlying cultural appropriation and colonial violence. The House of Two Sisters marks the arrival of a talented new voice who promises to contribute meaningfully to the genre’s ongoing evolution.