In the rubble-strewn streets of post-war Germany, where bombed-out buildings cast long shadows and hunger gnawed at the edges of survival, thousands of mixed-race children existed in a cruel limbo. Their American fathers had shipped out, and their German mothers faced impossible choices in a society that punished them for wartime romances. These children, dubbed “Brown Babies,” might have remained lost to history if not for extraordinary individuals who refused to let bureaucracy triumph over compassion.

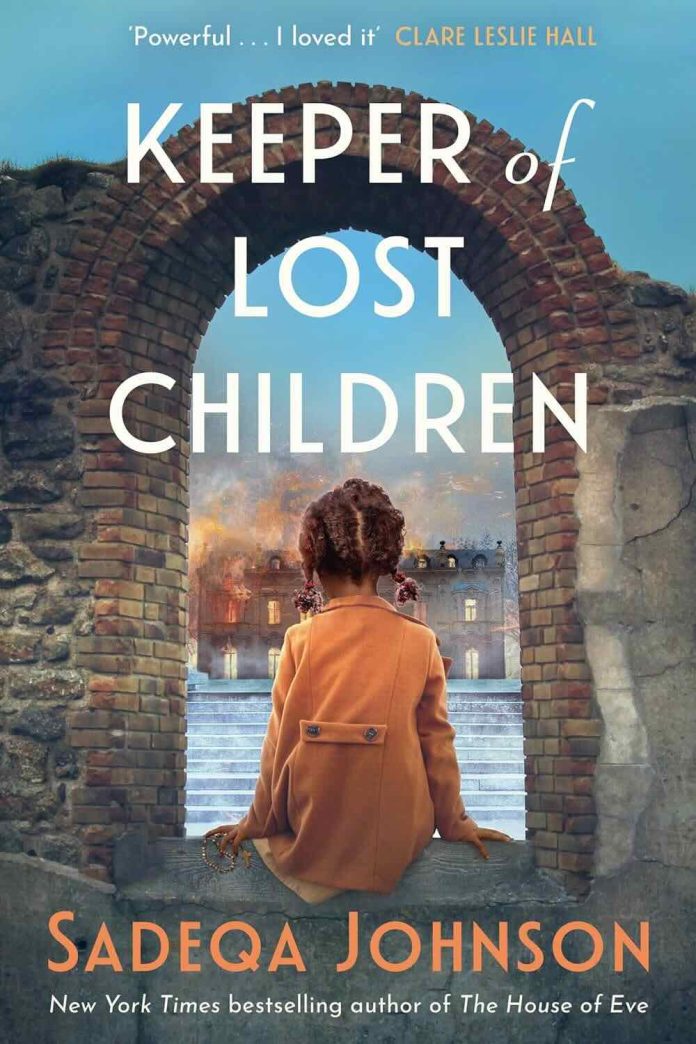

Keeper of Lost Children by Sadeqa Johnson excavates this overlooked chapter of history with the same meticulous care and emotional resonance that distinguished her previous works, The House of Eve and Yellow Wife. Johnson, a New York Times bestselling author known for illuminating marginalized women’s stories, once again demonstrates her remarkable ability to weave historical truth with intimate human drama. This latest novel alternates between three interconnected narratives spanning from 1948 to 1965, creating a meditation on identity, belonging, and the transformative power of maternal love in all its forms.

Three Lives, One Invisible Thread

The architecture of Keeper of Lost Children by Sadeqa Johnson rests on three pillars, each representing a distinct perspective on the Brown Baby phenomenon. Ethel Gathers, inspired by real-life adoption champion Mabel Grammer, arrives in Mannheim, Germany in 1950 as the wife of an Army warrant officer. Unable to bear children herself due to medical complications, Ethel channels her maternal yearning into something revolutionary: the Brown Baby Plan, a one-woman adoption agency that would eventually place over five hundred mixed-race children with loving families.

Johnson renders Ethel with complexity that elevates her beyond mere sainthood. She is driven, yes, but also flawed—her determination occasionally borders on missionary zeal, and her methods, while well-intentioned, sometimes prioritize efficiency over the messy realities of human relationships. The author doesn’t shy away from showing how even the most compassionate systems can produce unintended consequences, a nuance that gives the novel its moral weight.

Ozzie Philips represents the second narrative thread. A young Black soldier from Philadelphia who volunteers for the Army in 1948, Ozzie seeks to prove himself in a military freshly desegregated by Truman’s executive order. What he finds in Germany is a bittersweet freedom—liberated from America’s Jim Crow restrictions yet still encountering racism from white servicemen. His romance with Jelka, a German woman struggling in the war’s aftermath, produces a daughter, Katja. But army regulations, an absent husband’s potential return, and Ozzie’s own conflicted loyalties conspire to tear the family apart before it can truly form.

The third perspective belongs to Sophia Clark, who in 1965 becomes one of the first Black students to integrate West Oak Forest Academy, a prestigious Maryland boarding school. Sophia’s journey from a brutal existence on a Maryland farm to academic opportunity becomes a mystery of identity when she begins suspecting her adoption origins might trace back to Germany. Her search for truth forms the novel’s most propulsive storyline, even as it reveals the painful cost of secrets and administrative mix-ups.

The Craft of Connection

Johnson’s narrative structure deserves particular recognition. The alternating timelines could have felt disjointed, but instead they create a mounting sense of inevitability. Readers understand connections before the characters do, generating tension that propels the novel forward. The author employs this technique with precision, doling out revelations at a pace that satisfies without overwhelming.

The prose itself carries the weight of each era with authenticity:

- Post-war Germany sections are rendered in spare, almost stark language that mirrors the stripped-down landscape

- Ozzie’s chapters pulse with the rhythms of 1940s jazz and the coded language Black soldiers used to navigate white spaces

- Sophia’s boarding school experience captures the particular isolation of being a racial pioneer, where every interaction carries the burden of representation

Johnson’s research shines through without becoming pedantic. Details about military procedures, adoption bureaucracy, and the social codes of various communities feel lived-in rather than looked-up. The author clearly immersed herself in the documentary Brown Babies: The Mischlingskinder Story and numerous other sources, yet she wears her research lightly, allowing character and emotion to remain paramount.

Where the Novel Shines

The greatest strength of Keeper of Lost Children by Sadeqa Johnson lies in its refusal of simplistic narratives. German mothers aren’t villainized for giving up their children; instead, Johnson illuminates the impossible positions these women occupied in a devastated, judgmental society. Black soldiers aren’t portrayed as either heroes or villains, but as young men navigating complex moral terrain while facing discrimination both at home and abroad. Even Ethel, the novel’s closest approximation to a protagonist, makes decisions that haunt her—well-meaning mistakes that upend lives.

The supporting characters pulse with life. Julia Jones, Ethel’s friend among the military wives, provides both comic relief and emotional grounding. Max, Sophia’s classmate who shares her German adoption background, offers a mirror for her journey of self-discovery. Franz, one of Ethel’s adopted children who tries to scrub the brown from his skin, embodies the psychological toll of internalized racism in a single devastating scene.

Johnson also excels at depicting the microaggressions and casual cruelties that defined integration efforts. Sophia’s experience at West Oak Forest Academy rings painfully true—the fake slave auction in the locker room, the rumor about Negro students having tails, the subtle and not-so-subtle ways white classmates and teachers mark her as different. These scenes never feel gratuitous; they serve the larger narrative of identity formation under hostile scrutiny.

Critical Considerations

While Keeper of Lost Children by Sadeqa Johnson succeeds on multiple levels, it occasionally stumbles under the weight of its own ambitions. The three-perspective structure, while generally effective, sometimes results in uneven pacing. Ethel’s chapters, particularly in the middle section, can feel repetitive as she navigates bureaucratic obstacle after bureaucratic obstacle. The reader understands her determination, but watching her petition the same courts with the same arguments grows tedious.

Sophia’s storyline, the most contemporary of the three, sometimes feels rushed in comparison to the others. Her transformation from farm laborer to boarding school student to investigator of her own past happens at breakneck speed. More gradual development of her friendship with Willa and her romance with Max would have strengthened the emotional payoff of later betrayals and reconciliations.

The novel’s resolution, while emotionally satisfying, ties up loose ends with perhaps too neat a bow. Given the complexity Johnson establishes throughout, the convergence of all three storylines in the final chapters feels slightly contrived. Life’s messiness, which the author captures so well elsewhere, gives way to a more conventional narrative closure that, while earned, doesn’t quite match the nuanced realism of what came before.

Additionally, some readers might find Jelka, Ozzie’s German lover and Katja’s mother, remains somewhat underdeveloped compared to other characters. While her circumstances are clearly delineated, her interior life never comes into full focus. This may be a deliberate choice—we see her through Ozzie’s eyes and later through documentary evidence—but it creates an absence at the heart of one of the novel’s central relationships.

Thematic Resonance

At its core, Keeper of Lost Children by Sadeqa Johnson grapples with questions that remain urgent today:

- What constitutes family? The novel argues that biology matters less than commitment and love

- Who gets to define identity? Sophia’s journey illustrates how external forces—from adoption paperwork to racial categories—attempt to fix what should remain fluid and self-determined

- How do we reckon with well-intentioned harm? Ethel’s work saved lives but also severed connections; the book asks us to hold both truths simultaneously

- What does liberation look like for Black Americans? Ozzie’s experience in Germany suggests that true freedom requires more than legal changes

The title itself carries multiple meanings. Ethel is literally a keeper of lost children, but so too are the German mothers who reluctantly give up their babies, and even Sophia’s adoptive parents who “keep” her for economic purposes rather than love. Everyone in this novel is both keeper and kept, bound by systems larger than themselves yet responsible for the choices they make within those constraints.

Literary Companions

Readers who appreciate Keeper of Lost Children by Sadeqa Johnson will find resonance in several other works exploring similar themes. The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett examines identity, passing, and the long shadow of family secrets across generations. Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi traces the divergent paths of families separated by historical forces beyond their control. For those interested specifically in post-war Germany and occupation, Half-Blood Blues by Esi Edugyan offers another perspective on Black experience in wartime Europe. Sue Monk Kidd’s The Secret Life of Bees explores surrogate motherhood and found family in the Jim Crow South, while The Sweetness of Water by Nathan Harris examines interracial relationships and their consequences in post-Civil War America.

Final Reflections

Keeper of Lost Children by Sadeqa Johnson is ambitious historical fiction that succeeds more often than it stumbles. Johnson has gifted readers with an entry point into a forgotten history, populating it with characters who feel simultaneously specific to their moment and universally human. The novel’s emotional resonance comes not from manipulation but from earned pathos—we care about these people because Johnson has made them real.

The book serves as an important reminder that history’s margins contain stories worth excavating, that the women and children often relegated to footnotes shaped our world in profound ways. While the pacing occasionally lags and some plot mechanics creak under scrutiny, these are minor complaints about a work that dares to tackle complex themes with nuance and compassion.

For readers who appreciate historical fiction that challenges as it entertains, that educates without preaching, and that honors forgotten lives without sanctifying them, this novel delivers. Johnson continues to establish herself as one of our most important chroniclers of Black women’s experiences across time, and Keeper of Lost Children by Sadeqa Johnson stands as testament to the power of stories to recover what history tried to erase.