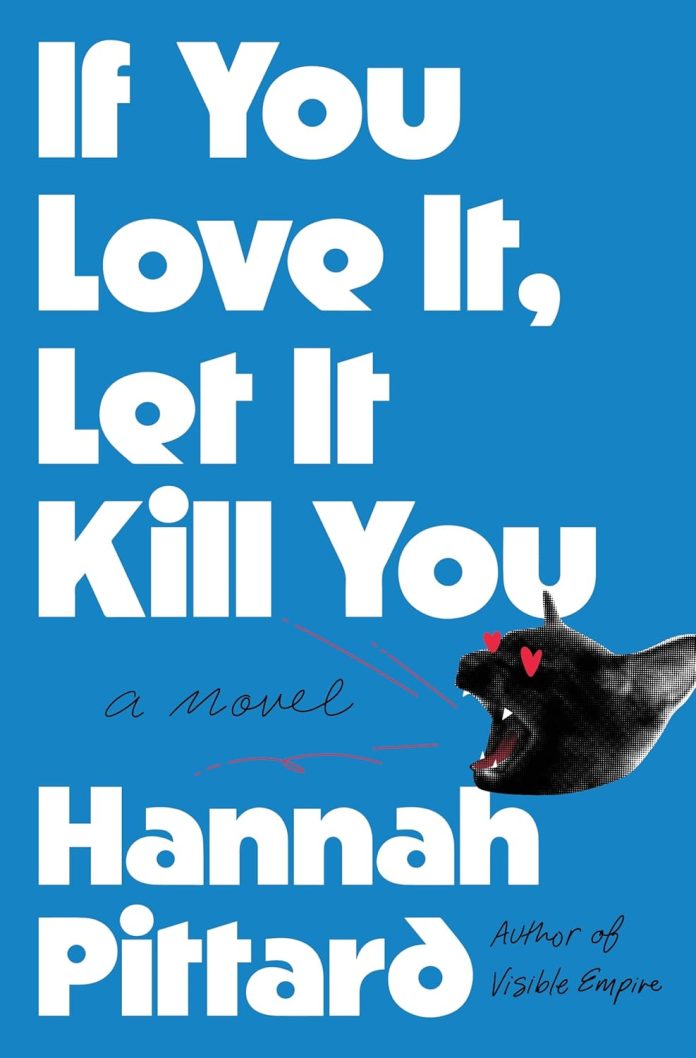

Hannah Pittard’s latest novel, If You Love It, Let It Kill You, arrives like a conversation you didn’t know you desperately needed to have. This isn’t your typical midlife crisis narrative—it’s far more sophisticated, darkly humorous, and uncomfortably relatable than that tired trope suggests. Pittard, author of The Fates Will Find Their Way and Visible Empire, has crafted her most personal and provocative work yet, one that dissects the peculiar anxieties of contemporary womanhood with surgical precision and unexpected tenderness.

The novel follows Hana, a creative writing professor whose carefully constructed life begins to unravel when she learns that her ex-husband has written her into his debut novel—and not flatteringly. What begins as a minor irritation blooms into something far more complex: a profound questioning of identity, ownership, and the stories we tell ourselves about our lives. The inciting incident might seem small, but Pittard understands that the most significant life changes often spring from seemingly insignificant moments.

The Architecture of Domestic Unraveling

What makes this novel particularly compelling is how Pittard constructs Hana’s world. She lives with Bruce, her bald, dependable boyfriend, and his eleven-year-old daughter in a house across the street from her sister’s family. Her parents, divorced for decades, have both relocated nearby, creating a constellation of complicated relationships that feel both suffocating and essential. Into this carefully balanced ecosystem comes the news of the ex-husband’s literary betrayal, and suddenly everything feels precarious.

The genius of Pittard’s approach lies in how she allows domestic details to carry emotional weight. The way Hana obsessively tracks Bruce’s banana waste, her elaborate dinner preparations, her surveillance of neighbors through binoculars—these aren’t quirky character traits but manifestations of deeper anxieties about control, purpose, and authenticity. The novel’s most profound insights often emerge from the mundane: folding laundry, grocery shopping, family dinners that stretch too long.

The Talking Cat and Other Brilliant Absurdities

One of the novel’s most audacious elements is the introduction of a talking cat—an injured tabby that Hana rescues and who becomes her unlikely confidant. This device could have felt gimmicky in less skilled hands, but Pittard uses it to explore themes of caretaking, moral responsibility, and the ways we project our own needs onto others. The cat serves as both comic relief and profound truth-teller, embodying the novel’s belief that wisdom often comes from unexpected sources.

The game of “Dead Body” that Hana plays with Bruce represents another stroke of brilliance. What begins as seemingly innocent role-playing becomes a meditation on vulnerability, trust, and the performance of relationships. These moments of physical comedy contain genuine intimacy, suggesting that sometimes we must play at being dead to remember what it means to be alive.

A Professor’s Nightmare: The Classroom Sequences

Pittard’s portrayal of academic life rings with uncomfortable authenticity. Hana’s interactions with her students, particularly the enigmatic Mateo, capture the delicate power dynamics of the contemporary classroom. The novel doesn’t shy away from exploring the ways #MeToo has complicated mentor-student relationships, but it does so with nuance rather than didacticism. When Hana faces complaints from her students about her teaching methods, the situation feels both inevitable and tragic—a collision of generational expectations and institutional paranoia.

The scenes in Hana’s creative writing workshops are particularly well-observed. Pittard, herself a professor, captures the peculiar intimacy of these spaces, where students reveal their deepest selves through fiction while teachers navigate the treacherous waters of critique and encouragement. The discussions of Hemingway’s “A Very Short Story” and Barthelme’s “The School” serve as more than mere literary references—they become mirrors for the novel’s own preoccupations with love, loss, and the stories we tell about both.

The Art of Literary Revenge

The novel’s central conceit—an ex-husband writing his former wife into his fiction—speaks to contemporary anxieties about consent, representation, and artistic freedom. Pittard explores these themes without offering easy answers. Is it ethical to mine one’s personal relationships for artistic material? What do we owe the people who become our characters? The novel suggests that these questions have no simple resolutions, only complicated negotiations between competing claims of truth and ownership.

Hana’s reaction to being “written” reveals layers of vulnerability and rage that feel deeply authentic. Her obsession with her ex-husband’s portrayal of her as “smug” and “insecure” speaks to the particular horror of being reduced to someone else’s interpretation of who you are. The novel’s most painful moments come when Hana recognizes uncomfortable truths in her ex-husband’s fictional version of her.

Family Dynamics and Generational Trauma

The novel’s exploration of family relationships is both hilariously dysfunctional and genuinely moving. Hana’s father, with his cowboy hat and manic energy, represents a particular type of charming but destructive masculinity. His journey from leather-working enthusiast to psychiatric patient is handled with remarkable sensitivity, avoiding both sentimentality and cruelty. The scenes where Hana picks him up from the Massachusetts facility are among the novel’s most powerful, revealing the ways adult children must sometimes parent their parents.

The relationship between Hana and Bruce’s daughter provides another emotional core to the novel. Pittard captures the particular challenges of step-parenting without the legal or social recognition that comes with marriage. The eleven-year-old’s gradual acceptance of Hana as a parental figure is both heartwarming and fraught with the possibility of loss.

Writing Style and Narrative Innovation

Pittard’s prose is consistently sharp and engaging, capable of moving seamlessly between comedy and pathos. Her use of present tense creates an immediacy that pulls readers into Hana’s increasingly frantic headspace. The novel’s structure—divided into five sections with titles like “The Joys of Slow Dismemberment”—reflects its protagonist’s mental state while maintaining narrative momentum.

The author’s decision to include meta-fictional elements, including imagined conversations with her students about the novel’s construction, adds another layer of sophistication. These moments feel organic rather than forced, contributing to the novel’s overall examination of artistic creation and responsibility.

Minor Criticisms and Structural Considerations

While “If You Love It Let It Kill You” succeeds on most levels, it occasionally feels overstuffed with incident. The subplot involving the Irishman from Hana’s past, while thematically relevant, sometimes feels disconnected from the main narrative thread. Similarly, some of the academic politics feel slightly exaggerated, though this may be intentional satire rather than oversight.

The novel’s ending, while satisfying, leaves some threads deliberately unresolved. This choice reflects the messiness of real life but may frustrate readers seeking more definitive closure. However, this ambiguity serves the novel’s larger themes about the impossibility of neat narrative resolution in actual human experience.

Contemporary Relevance and Universal Themes

If You Love It, Let It Kill You arrives at a moment when questions of artistic representation and personal agency feel particularly urgent. The novel’s exploration of middle-aged female identity resonates in an era when women are increasingly refusing to disappear gracefully into societal expectations. Hana’s crisis isn’t about aging or lost beauty—it’s about authenticity, purpose, and the courage to remain complicated in a world that prefers simple narratives.

“If You Love It Let It Kill You” also speaks to contemporary anxieties about domesticity and creative fulfillment. Hana’s comfortable life with Bruce represents a kind of success, but it’s a success that feels increasingly hollow. Pittard suggests that contentment, while valuable, isn’t the same as vitality—and that sometimes we must risk the things we love to discover who we really are.

A Worthy Addition to Contemporary Literature

If You Love It, Let It Kill You establishes Hannah Pittard as a major voice in contemporary fiction. The novel succeeds as both entertainment and serious literature, offering insights into the particular challenges of twenty-first-century womanhood while maintaining the wit and intelligence that made her previous works so compelling. It’s a book that rewards careful reading while remaining accessible to general audiences.

Similar Books You Might Enjoy

If you found yourself drawn to Pittard’s exploration of midlife crisis and creative anxiety, consider these comparable works:

- My Education by Susan Choi – Another novel about a woman questioning her domestic arrangements

- The Idiot by Elif Batuman – Campus novel with similar academic observations

- Weather by Jenny Offill – Fragmented narrative about contemporary female experience

- The Female Persuasion by Meg Wolitzer – Exploration of women’s ambitions and relationships

- Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill – Meditation on marriage, motherhood, and artistic identity

Hannah Pittard has created something genuinely special with If You Love It, Let It Kill You—a novel that manages to be both deeply personal and universally resonant, hilariously funny and profoundly moving. It’s the kind of book that will stay with you long after you’ve finished reading, continuing to reveal new layers of meaning with each consideration. In our current moment of cultural upheaval and personal uncertainty, Pittard offers something invaluable: the reassurance that complexity, contradiction, and restlessness aren’t character flaws but essential elements of a fully lived life.