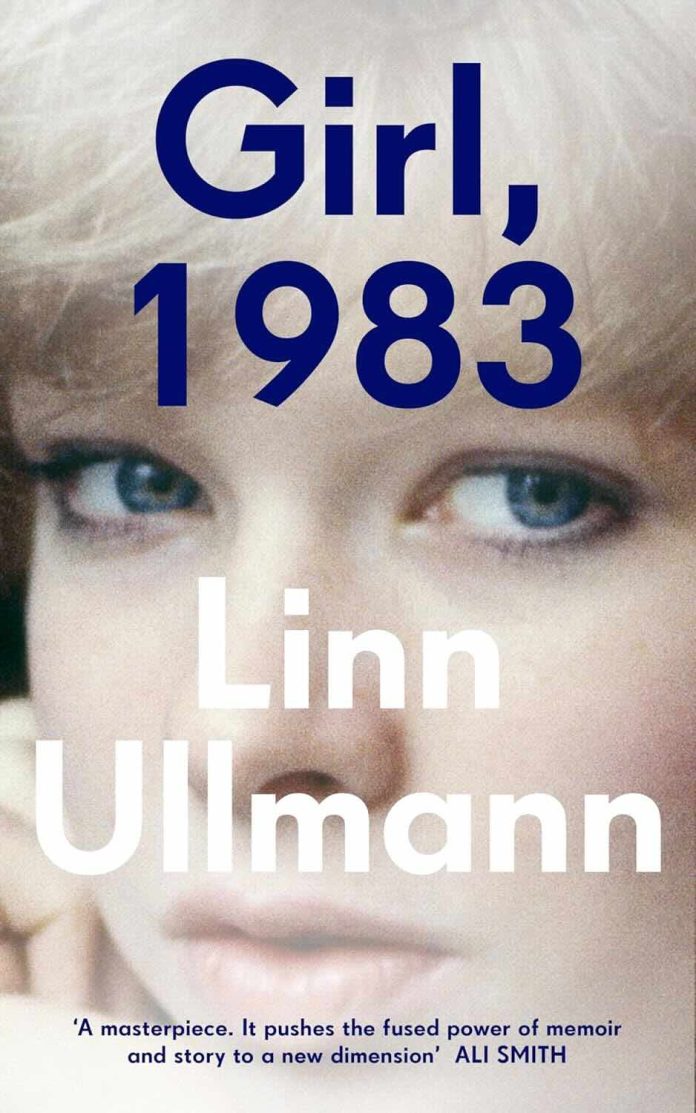

Linn Ullmann’s Girl, 1983 arrives as a crystalline yet fragmentary meditation on the treacherous territories of memory, desire, and the ways trauma reshapes the architecture of a life. This Norwegian author, daughter of filmmaker Ingmar Bergman and actress Liv Ullmann, has crafted what might be her most vulnerable and unflinching work—a novel that operates less as traditional narrative and more as an archaeological excavation of a sixteen-year-old girl’s devastating encounter with an older photographer in 1980s Paris.

The book follows two temporal threads: the unnamed narrator as a sixteen-year-old girl lost in the winter streets of Paris, carrying only a scrap of paper with the address of K, a forty-four-year-old photographer, and the same woman nearly four decades later, grappling with depression, anxiety, and the resurfacing of buried memories. What emerges is not a linear story but rather a kaleidoscopic examination of how certain moments can irrevocably alter the trajectory of a life.

The Architecture of Memory and Forgetting

Ullmann’s greatest achievement in Girl, 1983 lies in her masterful rendering of how memory functions—not as a reliable narrator but as a shifting, elusive presence that reveals and conceals in equal measure. The adult narrator frequently acknowledges the gaps in her recollection, the “splash of white paint where the face should be,” borrowing Anne Carson’s phrase to describe the untranslatable nature of certain experiences.

The fragmented structure mirrors the protagonist’s fractured relationship with her past. Ullmann employs a technique of repetition and variation, circling back to certain scenes—the elevator encounter, the hotel room, the photographer’s apartment—each time revealing new details or questioning previous assumptions. This approach creates an almost hypnotic rhythm that draws readers into the narrator’s obsessive need to understand what happened to her.

The novel’s tripartite structure, divided into sections titled “Blue,” “Red,” and “White,” suggests both the emotional landscape of the experience and the clinical coldness with which trauma can be examined. Each color carries symbolic weight: blue for the melancholy of memory, red for passion and violence, white for the blank spaces where words fail.

The Complexities of Power and Vulnerability

At its core, Girl, 1983 is an unflinching examination of power dynamics and the ways in which youth and inexperience can be exploited. The relationship between the sixteen-year-old narrator and K is portrayed with a disturbing authenticity that avoids sensationalism while never minimizing the harm done. Ullmann presents K not as a monster but as a recognizably human figure whose actions have devastating consequences—perhaps making him more terrifying than any caricature of evil.

The novel excels in its portrayal of how the girl becomes complicit in her own exploitation, not through any fault of her own but through the complex psychology of survival and the desire to be seen as mature and sophisticated. The narrator’s adult self reflects on this with a mixture of compassion and horror, understanding both the girl’s vulnerability and her agency within impossible circumstances.

Particularly powerful is Ullmann’s exploration of how trauma becomes internalized, how the girl begins to see herself through the eyes of her exploiters. The modeling world, with its reduction of young women to objects of consumption, becomes a metaphor for broader societal attitudes toward female sexuality and worth.

Literary Craftsmanship and Translation

Martin Aitken’s translation preserves the spare, almost clinical precision of Ullmann’s prose while maintaining its emotional resonance. The language is deceptively simple, often employing short, declarative sentences that accumulate power through repetition and careful placement. Ullmann has a gift for finding the exact detail that illuminates an entire emotional landscape—the blue tiles of a bathroom floor, the sound of a dog drinking water, the weight of a red woolly hat.

The novel’s experimental structure, with its time shifts and repetitions, could easily become pretentious or exhausting, but Ullmann maintains perfect control. The fragmentation feels organic to the subject matter rather than imposed, and the occasional breaks into lists or fragments serve to emphasize the narrator’s struggle to impose order on chaotic experience.

The integration of historical events—from the arrest of Nazi war criminal Klaus Barbie to Reagan’s “evil empire” speech—grounds the personal narrative in larger political contexts without overwhelming the intimate story. These references serve as temporal anchors and suggest connections between personal and collective trauma.

Emotional Resonance and Psychological Depth

Where Girl, 1983 truly succeeds is in its psychological authenticity. The adult narrator’s depression is rendered with devastating accuracy, from the physical sensation of “floating” above the ground to the exhaustion of maintaining a façade of normalcy. Ullmann captures the particular quality of trauma-related anxiety—the way past and present collapse into each other, how the body remembers what the mind tries to forget.

The relationship between the narrator and her mysterious “shadow-sister”—a presence that may be dissociation, creativity, or simple survival mechanism—adds another layer of complexity to the narrative. This figure represents both the narrator’s attempt to protect herself and her ongoing struggle with fragmentation and identity.

The novel’s exploration of mother-daughter relationships is equally nuanced. The narrator’s mother emerges as both protector and inadvertent enabler, loving but ultimately unable to prevent her daughter’s encounter with danger. Their phone conversations across time zones become poignant metaphors for the distances that trauma creates even within loving relationships.

Critical Considerations and Limitations

While Girl, 1983 is undeniably powerful, it is not without limitations. The experimental structure, while thematically appropriate, can occasionally feel repetitive rather than revelatory. Some readers may find the fragmentary approach frustrating, particularly those seeking narrative closure or clear resolution.

The novel’s intense focus on a single traumatic experience, while psychologically authentic, can feel claustrophobic. The narrator’s obsessive return to these events, while realistic, sometimes threatens to overwhelm other aspects of her life and development. Additionally, certain secondary characters, particularly the various men in the modeling world, can feel more like symbols than fully realized individuals.

The book’s meditation on memory and trauma, while profound, occasionally risks becoming overly cerebral. There are moments where the analysis of experience threatens to eclipse the experience itself, though Ullmann generally maintains the balance between reflection and immediacy.

Cultural and Literary Context

Girl, 1983 joins a growing body of Scandinavian literature exploring trauma, memory, and the lasting effects of abuse. It shares DNA with works like Vigdis Hjorth’s Will and Testament and Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, though Ullmann’s approach is more experimental and less linear than either.

The novel can also be read alongside Ullmann’s previous work, particularly Unquiet, which explored her relationship with her famous parents. Both books demonstrate her ability to transform personal material into universal examinations of family, memory, and identity. Her earlier novels, including Before You Sleep and Stella Descending, established her as a writer capable of profound psychological insight, but Girl, 1983 represents a new level of formal experimentation and emotional courage.

Final Assessment

Girl, 1983 is a significant achievement in contemporary literature, a novel that refuses to provide easy answers or false comfort. Ullmann has created a work that is simultaneously specific to one woman’s experience and universal in its exploration of how we survive our own histories. The book’s experimental structure serves its themes rather than overwhelming them, and its emotional honesty is both devastating and ultimately healing.

This is not a comfortable read, nor should it be. It is a necessary one—a reminder that literature at its best can help us understand the most difficult aspects of human experience. While the novel may not satisfy readers seeking traditional narrative pleasures, it offers something more valuable: a honest reckoning with the ways trauma shapes identity and the possibility of finding meaning in even the most painful experiences.

Similar Reading Recommendations

For readers drawn to Girl, 1983, consider these complementary works:

- My Struggle series by Karl Ove Knausgård – Another Norwegian exploration of memory and identity

- Outline trilogy by Rachel Cusk – Experimental novels examining selfhood and storytelling

- The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson – A genre-bending meditation on identity and transformation

- Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill – Fragmentary novel about marriage, motherhood, and artistic identity

- Memorial by Alice Oswald – Experimental poetry exploring trauma and remembrance

Girl, 1983 stands as a testament to literature’s capacity to transform pain into understanding, offering readers not resolution but recognition—the profound relief of seeing one’s own struggles reflected with honesty and artistry.