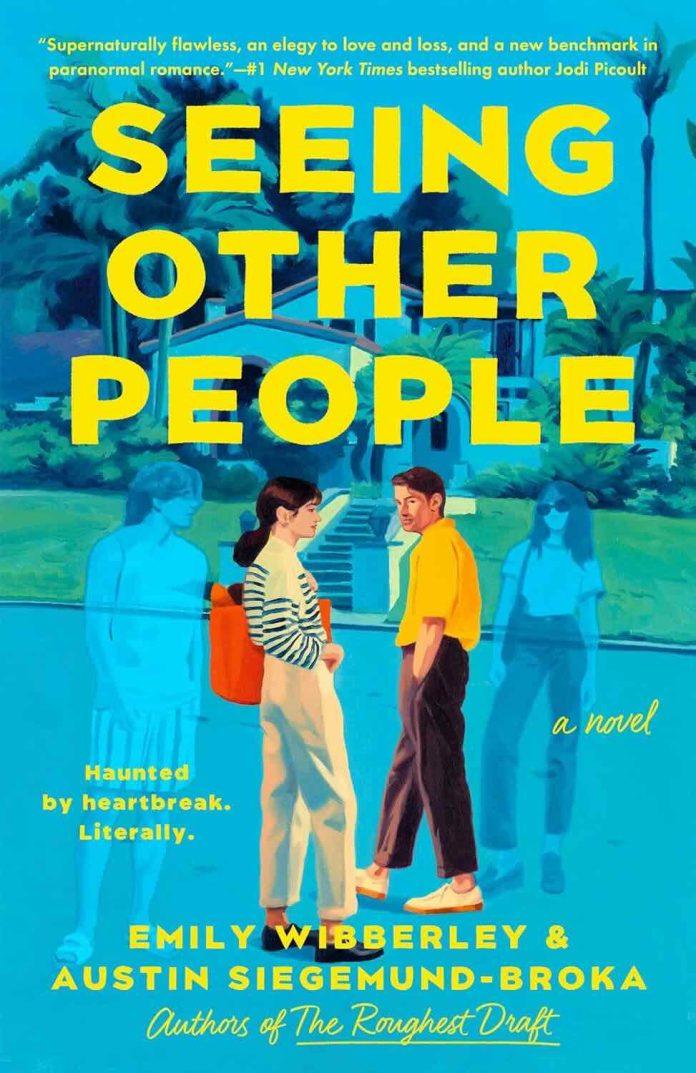

Emily Wibberley and Austin Siegemund-Broka venture into paranormal romance with Seeing Other People, crafting a story where ghosts become unexpected matchmakers and grief transforms into healing. This unique blend of contemporary romance and magical realism explores what it means to truly move forward when the past refuses to stay buried.

The Premise: More Than Just Paranormal Meets-Cute

Morgan Lane’s dating life has always been complicated, but being haunted by Zach—a guy she hooked up with once before he died—takes complications to supernatural levels. Her closet rattles ominously, her electronics malfunction at inopportune moments, and worst of all, Zach won’t stop offering commentary on her life choices. Desperate for a solution, she finds herself at a ghost support group where she meets Sawyer, a ceramicist who’s been living with his late fiancée Kennedy’s ghost for five years.

The setup immediately distinguishes itself from typical ghost stories. Rather than positioning the supernatural as something to fear or eliminate, Wibberley and Siegemund-Broka present haunting as a metaphor for how we all carry our pasts with us. Morgan wants Zach gone so she can reclaim her independence; Sawyer desperately clings to Kennedy’s presence, terrified of losing her completely. Their opposing problems create natural friction that evolves into genuine chemistry as they reluctantly join forces.

Character Development: Living Like Ghosts

The real haunting in this novel isn’t supernatural—it’s emotional. Both protagonists exist in states of self-imposed limbo that make them as spectral as their actual ghosts. Morgan has spent years running from commitment, convinced she’s a “liability” after dropping out of college and fleeing an engagement. She moves constantly, keeps possessions minimal, and treats relationships as temporary arrangements. Her fear of disappointing others has transformed into a lifestyle of preemptive abandonment.

Sawyer presents the opposite extreme. Five years after Kennedy’s death, he’s frozen his entire life in amber. Living off dwindling savings in their half-renovated dream house, he’s abandoned his pottery career, isolated himself from friends, and devoted himself entirely to preserving Kennedy’s memory. His haunting is both literal and self-inflicted—a comfortable prison of grief he’s terrified to leave.

The authors excel at showing rather than telling how damaged both characters are. Morgan’s single suitcase of belongings and inability to remember her past apartments speak volumes about her refusal to build a life. Sawyer’s house, with its completed rooms frozen as Kennedy left them and unfinished spaces he can’t bear to touch, becomes a perfect physical manifestation of arrested development. These aren’t quirky character traits but defense mechanisms born from genuine trauma.

Key character strengths include:

- Morgan’s fierce independence and practical competence (she’s genuinely skilled at landscaping)

- Her underlying vulnerability beneath the commitment-phobic exterior

- Sawyer’s gentle steadiness and capacity for deep love

- His artistic soul trapped beneath layers of grief

- Both characters’ growth feeling earned rather than convenient

The supporting ghosts—Zach and Kennedy—avoid the pitfall of being mere plot devices. Zach evolves from an annoying specter into Morgan’s unlikely friend, his easygoing surfer personality providing comic relief while his own journey toward accepting death adds emotional depth. Kennedy’s revelation that her unfinished business is ensuring Sawyer moves on represents one of the novel’s most poignant twists, transforming what could have been a romantic triangle into something far more nuanced.

The Romance: Slow-Burn Amidst Supernatural Chaos

The central romance develops with admirable patience. Initial antagonism gives way to reluctant cooperation, then genuine friendship, before romantic feelings emerge. The authors understand that two people this damaged can’t simply fall into easy love—they need time to learn trust, to see beyond their own pain, and to risk vulnerability again.

Their connection deepens through shared experiences: confronting Zach’s grieving father, renovating Sawyer’s haunted house, embarking on a road trip to scatter Zach’s memory at his favorite surf spot. Each milestone peels back another layer of their carefully constructed defenses. The chemistry builds naturally through small moments—Morgan teaching Sawyer about plants, Sawyer returning to pottery with Morgan watching, late-night conversations that reveal past wounds.

The physical progression feels appropriately gradual. Their first kiss, interrupted by Kennedy cutting the lights, captures the complexity of romance shadowed by grief. Sawyer’s confession that he hasn’t kissed anyone since Kennedy died adds weight to every intimate moment. When they finally come together, it feels like the culmination of genuine emotional connection rather than manufactured sexual tension.

However, the romance occasionally suffers from the characters’ communication issues feeling manufactured rather than organic. Both Morgan and Sawyer make choices driven more by plot necessity than authentic character motivation, particularly in the third act when misunderstandings create separation. The “big fight” that drives them apart relies heavily on Morgan keeping Kennedy’s secret about her unfinished business, a choice that makes logical sense but creates frustrating dramatic irony.

Setting and Atmosphere: Sunshine Haunts

Los Angeles becomes an unexpected but effective setting for a ghost story. The authors smartly contrast supernatural darkness with the city’s relentless sunshine, creating dissonance that mirrors their protagonists’ internal conflicts. Sawyer’s Silver Lake hillside home with its dead garden and dusty pottery studio feels genuinely haunted despite California’s bright optimism. Morgan’s West Hollywood apartment, cramped and temporary, reflects her transient existence.

The road trip to San Onofre provides crucial tonal variety, offering both romantic development and closure for Zach’s storyline. The beach setting—with its bonfires, surfing culture, and emphasis on living in the moment—contrasts beautifully with Sawyer’s static existence and Morgan’s perpetual motion. It’s where both characters must finally confront what moving forward actually means.

Specific locations like Harrison’s Hardware (where Zach’s father works) and various nurseries and pottery supply stores ground the story in concrete, sensory detail. The authors demonstrate genuine knowledge of both landscaping and ceramics, incorporating technical details that add authenticity without becoming tedious.

Themes: The Work of Moving On

At its core, Seeing Other People examines different forms of grief and stagnation. Sawyer’s obvious mourning for Kennedy contrasts with Morgan’s less recognizable grief for the life she abandoned and the person she might have become. Both have constructed elaborate coping mechanisms that keep them safe but prevent genuine living.

The novel’s central question—what does it mean to move on?—receives nuanced exploration. Moving on doesn’t mean forgetting Kennedy or erasing past mistakes. Instead, it means integrating loss into a life that continues forward. Sawyer creates an urn-turned-flowerpot for Kennedy’s ashes, planting lilies that will grow and change while honoring her memory. Morgan learns that commitment isn’t imprisonment but choosing to build something lasting despite uncertainty.

The theme of “putting down roots” runs throughout, literal in Morgan’s landscaping work and metaphorical in her emotional journey. Her transformation of Sawyer’s dead yard into flourishing gardens parallels her own growth from someone who runs at the first sign of difficulty to someone willing to cultivate a life that requires patience and care.

Structural Strengths and Weaknesses

The dual POV alternating between Morgan and Sawyer provides necessary balance, preventing either character from dominating the narrative. Both voices feel distinct—Morgan’s chapters carry more nervous energy and self-deprecating humor, while Sawyer’s are more introspective and emotionally measured.

The pacing generally works well, though the middle section occasionally stalls as the authors navigate the logistics of ghost investigation. Some sequences—particularly those involving research into Zach’s past or Kennedy’s fading—feel more functional than compelling. The final act rushes slightly, compressing what could have been more gradual character evolution into convenient realizations.

The handling of the supernatural elements strikes an effective balance between whimsy and emotion. Ghosts can manifest physically (Zach’s earthquake, Kennedy clearing the garden), provide comic relief (Zach’s obsession with specific songs), and deliver genuine pathos (both ghosts facing their own non-existence). However, the rules governing ghostly abilities remain somewhat inconsistent, with powers appearing or disappearing as plot demands.

The Emotional Landscape

Where Seeing Other People truly succeeds is in its emotional authenticity. The portrayal of grief feels lived-in rather than researched, capturing how loss doesn’t follow tidy timelines or neat stages. Sawyer’s description of fearing he’ll forget the smell of Kennedy’s hair or the sound of her sneezes resonates with genuine anguish. His admission that he scours his phone for photos and videos, desperate for proof of memories already fading, will strike familiar chords for anyone who’s lost someone.

Similarly, Morgan’s fear of commitment stems from recognizable self-loathing rather than simple flightiness. Her belief that she’s a “liability” who ruins others’ lives through her choices feels painfully real, especially for readers who’ve struggled with feeling like they can’t get life “right” compared to others.

The supporting cast adds depth to this emotional landscape. Zach’s father, still grieving his son years later, provides heartbreaking moments when Sawyer helps him remember details of Zach’s hands. Zach’s sister and his Perfect Weekend surf crew show how death ripples through communities. Even minor characters like Savannah (Morgan’s exasperated roommate) feel like real people rather than plot furniture.

Critiques Worth Noting

Despite its strengths, Seeing Other People stumbles in several areas. The resolution feels somewhat rushed, with Sawyer’s breakthrough in letting Kennedy go happening too quickly after 400+ pages of resistance. The mechanics of how both ghosts finally move on remain vague, relying on emotional catharsis rather than internal logic.

Morgan’s character arc, while satisfying, occasionally veers into familiar “commitment-phobic woman learns to stay” territory. Her past relationship with Michael and the broken engagement feel underexplored considering how formative that experience supposedly was. More details about her college dropout decision and the aftermath would have strengthened her characterization.

The dialogue sometimes tries too hard for witty banter, resulting in exchanges that feel scripted rather than spontaneous. Characters occasionally deliver speeches that work better as thematic statements than natural conversation. The balance between humor and heaviness doesn’t always land smoothly, with tonal shifts sometimes feeling abrupt.

The ghost support group, while providing an effective meeting place for Morgan and Sawyer, never quite fulfills its narrative potential. Other attendees remain one-dimensional, existing primarily to highlight how “real” our protagonists’ hauntings are by comparison. A subplot involving the support group leader’s crystal-selling hustle goes nowhere meaningful.

Similar Reads for Romance Readers

Readers drawn to Seeing Other People might enjoy:

- Cemetery Boys by Aiden Thomas – Young adult paranormal romance dealing with ghosts, identity, and acceptance

- The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue by V.E. Schwab – Magical realism exploring memory, legacy, and what it means to be remembered

- Midnight at the Bright Ideas Bookstore by Matthew Sullivan – Mystery-tinged romance about confronting painful pasts

- The Dead Romantics by Ashley Poston – Contemporary romance featuring a ghostwriter who can see ghosts, similar tone

- Beach Read by Emily Henry – Dual POV romance between two wounded writers healing together

- The Roughest Draft by Emily Wibberley and Austin Siegemund-Broka – The authors’ previous adult romance featuring former writing partners reconnecting

Final Verdict

Seeing Other People succeeds as both paranormal romance and grief narrative, though it excels more at the latter than the former. Wibberley and Siegemund-Broka bring genuine emotional intelligence to their exploration of loss, commitment, and the courage required to build a life after everything falls apart. While the romance sometimes takes narrative backseat to character healing, readers seeking substance alongside their love story will find much to appreciate.

Seeing Other People works best for readers who enjoy character-driven romances where internal growth matters as much as relationship development. Those seeking primarily escapist paranormal romance might find the grief themes heavier than expected, while readers wanting pure comedy will need to embrace substantial emotional weight. The sunny Los Angeles setting and occasional levity prevent the story from becoming oppressively sad, but this remains fundamentally a book about learning to live again after loss.

The authors demonstrate impressive range in transitioning from young adult to adult romance while adding speculative elements to their contemporary foundation. Their prose maintains clarity and emotional resonance without sacrificing sophistication. Fans of their previous work will recognize their signature blend of humor, heart, and genuine understanding of relationships under pressure.

For readers willing to embrace both laughter and tears, supernatural whimsy and authentic grief, Seeing Other People offers a rewarding journey through love’s ability to exist alongside loss—and perhaps because of it.