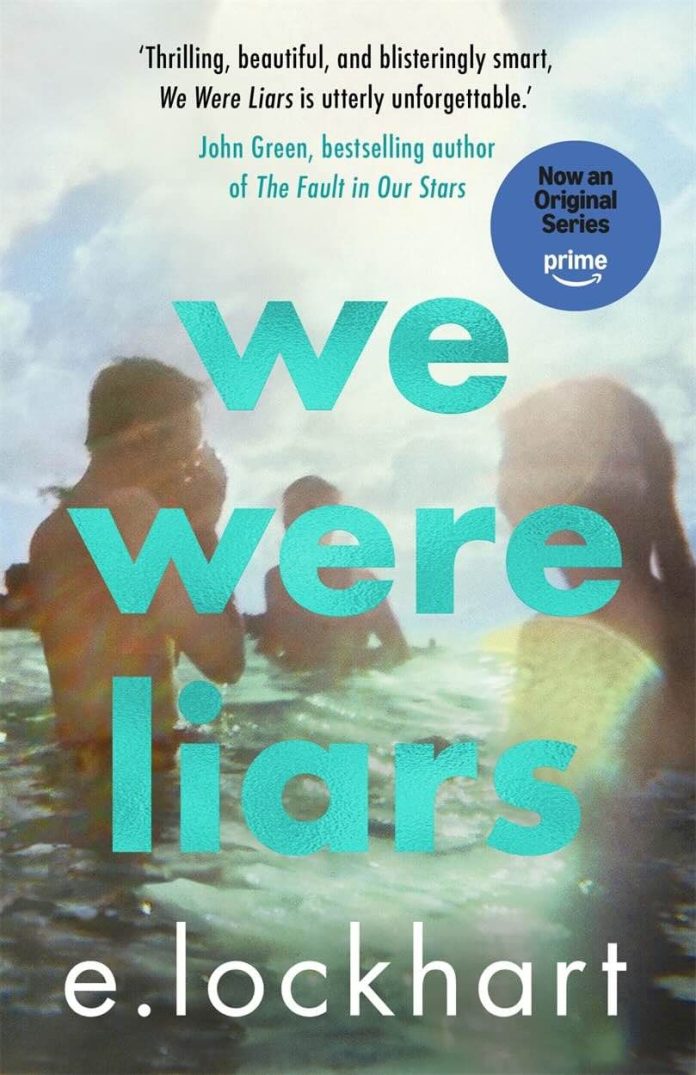

A private island off the coast of Massachusetts. Golden retrievers and golden children. Tennis whites and trust funds. The Sinclair family appears to have everything—wealth, beauty, privilege wrapped in cashmere and displayed in pearls. But beneath the carefully curated perfection lies something rotten, something that will burn everything to the ground. E. Lockhart’s We Were Liars is not merely a young adult novel; it is a masterclass in unreliable narration, a psychological thriller wrapped in the gauze of summer romance, and ultimately, a meditation on how the lies we tell ourselves can become more dangerous than any truth.

Published in 2014, this standalone novel—which has since expanded into a trilogy with Family of Liars (2022) and the upcoming We Fell Apart—remains one of contemporary YA literature’s most polarizing and unforgettable works. It demands to be read twice: once for the story you think you’re getting, and once for the story that was always there, hiding in plain sight.

The Architecture of Memory and Loss

Cadence Sinclair Eastman is seventeen, suffering from crippling migraines and selective amnesia following a mysterious accident during summer fifteen on Beechwood Island. The narrative unfolds across two timelines: the present summer seventeen, when Cadence returns to the family compound after two years away, and fragments of summer fifteen that emerge like photographs developing in a darkroom—blurry at first, then devastatingly clear.

Lockhart’s prose operates like Cadence’s fractured memory itself. The writing is staccato, repetitive, circular. Sentences fragment. Thoughts interrupt themselves. This isn’t carelessness; it’s architectural brilliance. The style mirrors traumatic brain injury, mirrors grief, mirrors the way we protect ourselves from unbearable truths by looking away, again and again, until we can’t anymore. When Cadence says, “I suffer migraines. I do not suffer fools. I like a twist of meaning,” we’re introduced to her wit, her pain, and the fundamental unreliability that will define our journey through her story.

Beautiful, Terrible People

The Sinclairs are “old-money Democrats” who summer on their private island, where patriarch Harris Sinclair built houses for his three daughters: Windemere for Penny, Red Gate for Carrie, Cuddledown for Bess. These aren’t just homes; they’re kingdoms in a feudal system where love is conditional, inheritance is currency, and appearing perfect matters more than being whole.

Cadence belongs to the “Liars”—a quartet consisting of her cousins Johnny and Mirren, and Gat, the nephew of Aunt Carrie’s boyfriend. They are bounce and snark, sugar and rain, passion and politics. During their summers together, they become something more than family, something closer than friends. They become co-conspirators in the revolution against their own privilege.

Lockhart excels at depicting the particular toxicity of wealthy families who measure love in real estate and judge worth by bloodlines. Gat, who is Indian-American, faces microaggressions disguised as politeness. The aunts weaponize their mother’s belongings, fighting over black pearls and embroidered tablecloths while their children watch the family corrode from within. It’s a pointed critique of how inherited wealth corrupts familial bonds, turning daughters into competitors and grandchildren into pawns.

Fairy Tales as Forensic Evidence

One of the novel’s most distinctive features is Cadence’s practice of writing fairy tale variations—retellings of classic stories that run parallel to her own narrative. These aren’t mere decoration. They function as both foreshadowing and psychological revelation, showing us what Cadence knows but cannot yet consciously access.

A king with three daughters. A dragon that destroys. A witch who burns what she most admires. These variations echo through the text like prophecies, and retrospectively, they read like confessions. Lockhart, who previously wrote The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks (a National Book Award finalist that similarly examines privilege and power), understands how we use stories to process trauma we can’t face directly. The fairy tales aren’t escape; they’re evidence.

The Romance That Devastates

The love story between Cadence and Gat provides the novel’s emotional core while also serving its thematic purpose. Their relationship exists in the context of class difference, racial prejudice disguised as family tradition, and the impossible dream of loving someone when your family sees them as fundamentally other. Gat reads Sartre and questions everything. Cadence adores him with the intensity of first love magnified by summers of longing.

But this isn’t a romance novel. The love story matters because it reveals how the Sinclair family’s dysfunction poisons everything it touches. When privilege meets genuine connection, when inherited prejudice confronts chosen family, something has to break. Lockhart never lets us forget that personal relationships don’t exist in a vacuum—they’re shaped by power, by money, by who gets to belong and who doesn’t.

The Truth, And Other Variations

To discuss what makes We Were Liars truly exceptional requires acknowledging its devastating final act without spoiling it. Suffice to say: this is a novel about the stories we tell ourselves to survive, and what happens when those stories finally fail. The twist—and there is one, though calling it merely a “twist” diminishes its psychological sophistication—recontextualizes everything that came before.

Some readers find this revelation earned and shattering. Others feel manipulated, arguing the narrative withholds information to manufacture surprise rather than building toward genuine revelation. Both reactions are valid. What’s undeniable is that Lockhart plants her clues meticulously, plays fair with attentive readers, and creates a second-read experience that is entirely different from the first. Details that seemed innocuous become loaded with meaning. Conversations reveal themselves as something other than what they appeared.

The novel’s final sections, when truth can no longer be denied, demonstrate Lockhart’s skill at depicting grief that hasn’t yet learned its own shape. This is where the book transcends its genre constraints and becomes literature about trauma, memory, and the impossible weight of survival.

The Weight of Words

Lockhart’s background in writing for young adults (the Ruby Oliver quartet, Fly on the Wall) prepared her for We Were Liars, but nothing in her previous work quite matches this novel’s formal daring. The prose is simultaneously sparse and lush, creating atmosphere through absence as much as presence. She writes in fragments:

“Welcome to the beautiful Sinclair family. No one is a criminal. No one is an addict. No one is a failure.”

“Be a little kinder than you have to.”

“Silence is a protective coating over pain.”

These aren’t just pretty sentences. They’re structural elements that create the novel’s unique rhythm—part incantation, part confession, part elegy. The repetitions, the returns to certain phrases, the way the narrative circles back on itself: these techniques mirror both Cadence’s damaged memory and the circular nature of family dysfunction, where the same patterns replay across generations.

Critiques and Considerations

The novel isn’t without weaknesses. Some readers find the prose style affected, the fragmentation more mannered than meaningful. The privileged setting may alienate readers for whom the Sinclair family’s problems feel impossibly remote. And the revelation that anchors the final act, while carefully constructed, can feel manipulative rather than illuminating depending on your tolerance for narrative unreliability.

Additionally, while the book tackles issues of class, privilege, and racial microaggressions, some critics argue these themes ultimately serve the plot rather than receiving the deep examination they deserve. Gat’s experiences with subtle racism, for instance, could have been explored with more nuance rather than functioning primarily as motivation for the Liars’ rebellion.

The Series Context

We Were Liars originally stood alone, but Lockhart returned to Beechwood Island with Family of Liars in 2022, a prequel exploring an earlier generation’s summer of secrets. The trilogy concludes with We Fell Apart, which promises to complete the multi-generational saga. For readers devastated by Cadence’s story, these companion novels offer both answers and new mysteries, expanding our understanding of how family trauma echoes across time.

For Readers Who Loved This

If We Were Liars captured you, consider:

- The Raven Boys by Maggie Stiefvater – atmospheric, character-driven, with deep friendship dynamics

- I’ll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson – fragmented narrative, family secrets, literary prose

- We Were the Lucky Ones by Georgia Hunter – different genre but similar title energy and family focus

- The Secret History by Donna Tartt – privileged students, devastating secrets, unreliable narration

- The Girls by Emma Cline – coming-of-age with a dark undercurrent

- Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng – family dysfunction, mystery, layered storytelling

Final Verdict

We Were Liars succeeds brilliantly at what it attempts: creating a reading experience that changes depending on what you know, when you know it, and how you piece together fragmented truths. It’s a novel about privilege examining itself, about love tested by prejudice, about truth and the lies we tell to survive it.

The book won’t work for everyone. Its stylistic choices divide readers. Its twist can feel either masterful or manipulative. But for those it captures, We Were Liars becomes unforgettable—the kind of book you press into friends’ hands with the instruction to “just read it” and refuse to answer any questions.

Years after publication, it remains a landmark of contemporary YA literature, proving that young adult fiction can be experimental, can refuse easy consolation, can trust its readers to handle devastating truths. Lockhart doesn’t just tell us a story; she makes us complicit in its unfolding, in its terrible beauties and beautiful terrors.

In the end, We Were Liars is exactly what its title promises: a book about beautiful people who lie, about the stories that both save and destroy us, and about what remains when everything burns. Read it once for the story. Read it twice for the truth. And then, perhaps, a third time for all the clues you missed—the evidence of disaster hiding in every sun-drenched summer afternoon, in every kiss, in every variation of every fairy tale about children who play with fire.