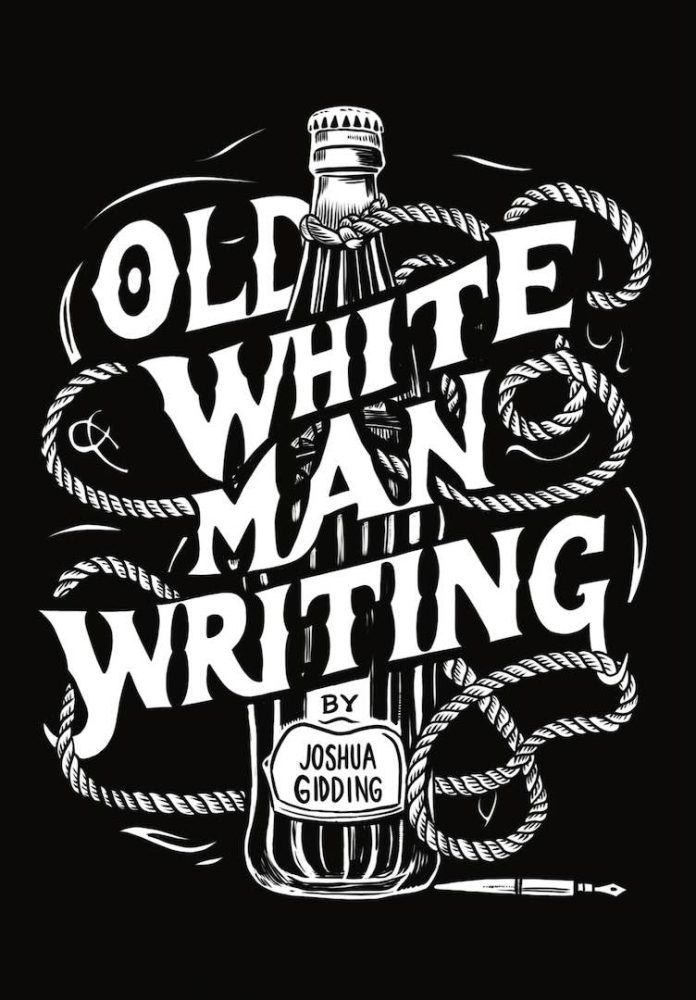

In an era where confessional writing risks becoming performative virtue-signaling, Joshua Gidding’s Old White Man Writing emerges as a masterclass in authentic self-scrutiny. This memoir transcends the typical boundaries of autobiographical writing by employing a brilliant literary device that transforms personal reflection into something approaching art. Gidding doesn’t merely examine his life—he dissects it with surgical precision, aided by one of the most innovative narrative techniques in contemporary memoir writing.

The Architecture of Consciousness

What sets Old White Man Writing apart from the crowded field of contemporary memoirs is its sophisticated dual-narrator structure. Gidding introduces us to Joßche, a fictional German literary biographer with a titanium membrane in his skull from a childhood bicycle accident. Far from being a mere literary gimmick, Joßche functions as Gidding’s intellectual conscience, a progressively critical voice that refuses to let the author off the hook for his privileged assumptions and comfortable liberalism.

The interplay between these two voices creates a kind of literary jazz improvisation, where Gidding’s narrative attempts at self-justification are consistently challenged by Joßche’s sharper, more cynical observations. This technique allows Gidding to avoid the trap of either excessive self-flagellation or defensive rationalization. Instead, we witness a genuine internal dialogue that mirrors the complexity of honest self-reflection.

The prose itself bears the unmistakable mark of a seasoned literary craftsman. Gidding, who previously authored the memoir Failure: An Autobiography (2007), writes with the accumulated wisdom of someone who has spent decades studying literature and teaching writing. His sentences carry the weight of classical education—he was a classics major at Berkeley and holds a PhD in English—yet remain accessible and engaging. The frequent Latin phrases and literary allusions never feel pretentious but rather emerge naturally from a mind steeped in literary tradition.

Wrestling with Privilege and Racial Consciousness

The memoir’s central preoccupation is Gidding’s attempt to reckon with his privileged white male identity in contemporary America. Having grown up in Pacific Palisades as the son of a screenwriter, attended Exeter and Berkeley, and spent his career in academia, Gidding embodies precisely the demographic that has become a lightning rod in current cultural discourse. Rather than defensively retreating from this reality, he leans into the discomfort it creates.

His examination of racial consciousness is particularly nuanced. Through a series of carefully rendered anecdotes—his family’s Black gardener Willie Dillard, whom he barely spoke to in thirteen years despite Willie working for the family; his mortifying behavior at Herb McCarthy’s restaurant; his participation in a Whiteness Awareness Study Group in Seattle—Gidding maps the geography of his own racial blind spots with unflinching honesty.

What makes these confessions compelling rather than merely self-indulgent is Joßche’s persistent questioning of Gidding’s motives. When Gidding recounts his racial missteps, Joßche interjects to ask whether this confession itself isn’t just another form of virtue-signaling. This self-reflexive quality prevents the memoir from becoming either a simple mea culpa or a defensive justification.

Love, Loss, and the Mathematics of Grief

Perhaps the book’s most emotionally resonant sections deal with Gidding’s relationship with his first wife Diane and her death from cancer in 2004. These passages reveal Gidding at his most vulnerable and literary. His description of their final months together, particularly the harrowing account of bringing Diane home from hospice care to die, achieves a level of emotional authenticity that recalls the best of Joan Didion’s writing about grief.

The eleven-year period of widowerhood that followed becomes what Gidding calls his “Minor Period,” and his exploration of this time reveals the memoir’s deeper philosophical concerns about biography and who deserves to have their story told. This period of solitude and reflection ultimately led to his relationship with his current wife Julie, but more importantly, it crystallized his understanding of what it means to survive and continue creating meaning after profound loss.

The Question of Biographization

One of the memoir’s most intriguing concepts is Gidding’s theory of “biographization”—the process by which a life becomes worthy of biographical treatment. This idea emerges from his reflection on Henry James’s concept of having a “Major Period” and evolves into a broader meditation on whose stories matter in contemporary culture. The question becomes particularly pointed when filtered through current discussions about diversity in publishing and storytelling.

Gidding doesn’t claim that his story as an “old white man” deserves special attention, but he does argue for the value of examining even privileged lives with sufficient depth and honesty. His approach suggests that the problem isn’t necessarily who tells stories, but how those stories are told and what insights they offer about the human condition.

Literary Craftsmanship and Stylistic Innovation

Gidding’s background as both a novelist and academic shows in every paragraph. His prose moves fluidly between high literary discourse and conversational intimacy. He can shift from quoting Virgil in Latin to describing the mundane details of daily life without missing a beat. This stylistic range serves the memoir’s thematic concerns, as it allows him to approach his material from multiple angles—philosophical, psychological, cultural, and deeply personal.

The Joßche device, while reminiscent of Philip Roth’s use of alter egos in works like Operation Shylock, feels fresh and necessary here. Unlike Roth’s more theatrical constructions, Joßche serves a genuinely critical function, pushing Gidding toward greater honesty and self-awareness. The result is a memoir that achieves the rare feat of being both deeply personal and intellectually rigorous.

Comparative Context and Literary Merit

Old White Man Writing stands alongside the finest contemporary memoirs in its willingness to interrogate the very act of memoir writing itself. It shares DNA with works like Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage in its meta-literary self-consciousness and with Karl Ove Knausgård’s My Struggle series in its unflinching examination of privilege and masculinity. However, Gidding’s work is more compact and focused, avoiding both Dyer’s digressive playfulness and Knausgård’s occasionally exhausting detail.

For readers familiar with Gidding’s earlier work Failure: An Autobiography, this memoir represents a significant evolution. Where the earlier book focused on professional and creative disappointments, Old White Man Writing takes on larger questions of social responsibility and cultural positioning. It’s the work of a writer who has found his mature voice and isn’t afraid to use it to examine uncomfortable truths.

Essential Reading for Our Cultural Moment

Old White Man Writing arrives at precisely the right cultural moment. At a time when discussions about privilege, race, and cultural responsibility often devolve into simplistic talking points, Gidding offers something far more valuable: a model for how to engage in genuine self-examination without either defensiveness or performative guilt. His willingness to be both challenged and challenging makes this memoir essential reading for anyone interested in how we might have more nuanced conversations about identity and responsibility in contemporary America.

The book’s humor—dry, self-deprecating, and often genuinely funny—prevents it from becoming ponderous despite its serious themes. Gidding has mastered the difficult art of being simultaneously serious and entertaining, a quality that makes the memoir’s insights more palatable and therefore more likely to actually influence readers’ thinking.

This is memoir writing at its finest: honest, intelligent, beautifully crafted, and genuinely illuminating. Gidding has created a work that speaks to our current cultural moment while transcending the limitations of mere topicality. It’s a book that will reward multiple readings and continue to reveal new layers of meaning as our cultural conversations evolve.

Similar Books Worth Reading

For readers drawn to Old White Man Writing, several other works explore similar themes with comparable literary sophistication:

- White Like Me by Tim Wise – A more directly political examination of white privilege

- Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates – Essential counterpoint perspective on race in America

- My Education by Susan Choi – Another memoir that interrogates the writer’s assumptions and privileges

- The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson – Genre-bending memoir that questions identity categories

- Heavy by Kiese Laymon – Powerful examination of race, class, and family in the American South

- In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado – Innovative memoir that experiments with form and perspective

Old White Man Writing deserves its place among the year’s most significant literary achievements. It’s a book that doesn’t just tell a story—it models a way of thinking about ourselves and our place in the world that we desperately need more of in contemporary discourse.