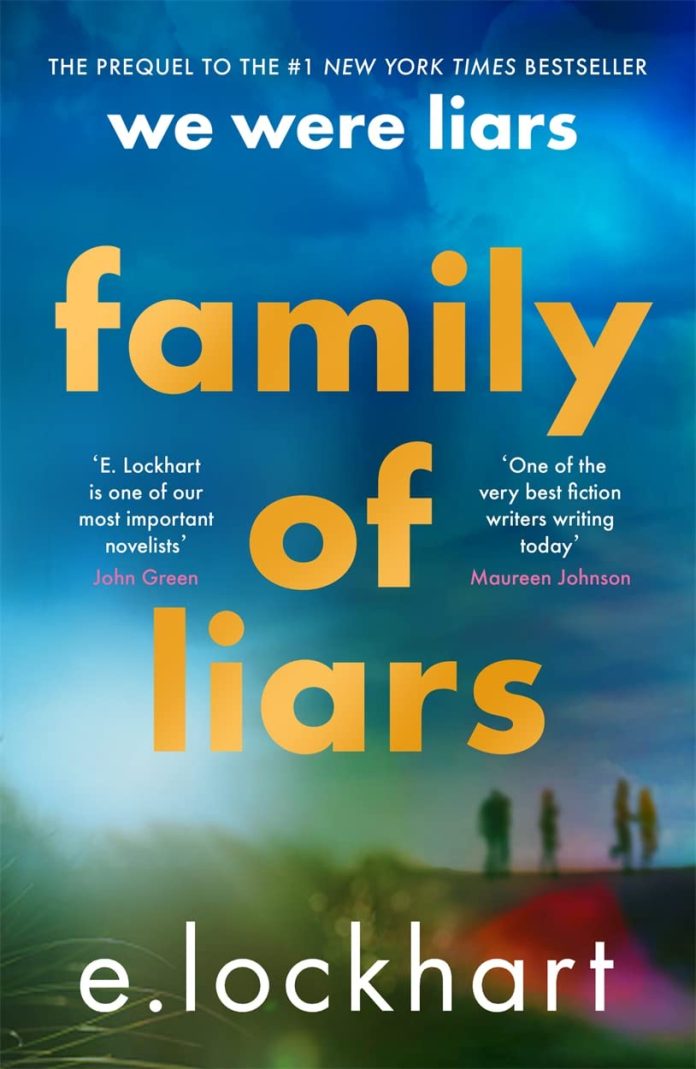

E. Lockhart invites readers back to the wind-swept shores of Beechwood Island with Family of Liars, a prequel to her explosive bestseller We Were Liars. This time, we venture into 1987, where seventeen-year-old Carrie Sinclair—mother to the original novel’s Johnny—narrates a summer that will reshape everything we thought we knew about the beautiful, terrible Sinclair family. Set against the backdrop of crashing waves and pristine beaches, Lockhart crafts a story that’s part mystery thriller, part coming-of-age romance, and entirely devastating.

The We Were Liars trilogy now includes We Were Liars (2014), Family of Liars (2022), and the upcoming We Fell Apart, creating a multi-generational exploration of one family’s capacity for both love and destruction. While Family of Liars stands alone, readers familiar with the original will find additional layers of tragic irony woven throughout.

The Architecture of Beautiful Lies

Lockhart’s prose remains her greatest weapon. She writes in fragments. Short bursts. Repetitions that hammer home emotional truths. The style mirrors Carrie’s fractured psyche—a girl trying desperately to hold herself together while everything around her unravels. This isn’t flowery young adult fiction; it’s sharp-edged literary craft disguised as a beach read.

The narrative structure deserves particular attention. Carrie tells her story to the ghost of her dead son Johnny, who visits her kitchen late at night asking questions about her youth. This framing device adds Gothic weight to what might otherwise feel like a straightforward summer romance. The present-tense intrusions remind us constantly that this beautiful summer has consequences that echo for decades.

Lockhart weaves fairy tale retellings throughout the narrative—particularly “Cinderella,” “Mr. Fox,” and a German tale about stolen pennies. These stories function as both foreshadowing and commentary, allowing Carrie to process experiences she cannot yet articulate directly. It’s a clever technique that adds mythic resonance to a deeply personal story, though some readers may find the repeated fairy tale interruptions slow the pacing.

The Sinclairs: Beautiful, Terrible People

The Sinclair family dynamics pulse with toxic authenticity. Three sisters—Carrie, Penny, and Bess—navigate the complicated waters of sibling rivalry, desperate love, and the crushing weight of family expectations. Lockhart captures how privilege simultaneously protects and imprisons, how “ugly money” from sugar plantations and exploitative publishing empires creates a gilded cage these young women cannot escape.

What makes this novel particularly powerful is its unflinching examination of complicity. The Sinclairs are not simply victims of their circumstances; they actively perpetuate harm while convincing themselves they’re good people. Carrie’s struggle with prescription drug addiction, her desperate need for her father’s approval, and her willingness to compromise her values for family acceptance create a protagonist who’s deeply flawed yet achingly human.

The introduction of Pfeff, Major, and George—three boys who crash into the sisters’ insular summer world—catalyzes everything. Pfeff particularly emerges as a character of contradictions: charming and reckless, generous and entitled, capable of both tenderness and cruelty. The romance between Carrie and Pfeff develops with the intoxicating intensity of first love, making the eventual betrayal cut deeper.

Where the Novel Excels

The atmosphere is masterful. Lockhart transforms Beechwood Island into a character itself—simultaneously paradise and prison. The contrast between sun-drenched beaches and dark secrets creates persistent unease. You can taste the salt air, feel the worn wooden walkways beneath your feet, hear the ocean’s constant churning.

The emotional complexity never wavers. This isn’t a simple story of good versus evil. Every character contains multitudes. Carrie’s desperate attempt to be “a credit to the family” while fighting addiction demonstrates how systems of privilege trap even those who benefit from them. The sister dynamics—shifting alliances, petty cruelties, fierce loyalties—feel painfully real.

Lockhart’s exploration of unreliable narration remains sophisticated. Carrie explicitly admits she’s a liar from the opening pages, yet we still trust her, still fall for her version of events. The slow revelation that she’s been shaping the narrative all along delivers a gut-punch that rivals the original novel’s infamous twist.

Where It Stumbles

Despite its considerable strengths, Family of Liars isn’t without weaknesses that prevent it from achieving the legendary status of its predecessor:

- Pacing issues in the middle sections: The novel occasionally meanders, particularly during extended sequences of daily island life. While these moments establish atmosphere, they sometimes feel repetitive. Readers expecting the propulsive momentum of We Were Liars may find themselves impatient.

- The ghost framing device feels underdeveloped: Johnny’s appearances provide narrative structure but lack the emotional depth they deserve. He asks questions but rarely challenges Carrie’s self-serving interpretations. More push-back from this spectral presence could have elevated the entire framework.

- Some thematic elements lack subtlety: The fairy tale parallels, while intellectually interesting, occasionally bludgeon rather than illuminate. Lockhart trusts her readers less here than in previous work, over-explaining connections that perceptive audiences would grasp independently.

- The romance doesn’t quite earn its emotional weight: While Pfeff and Carrie’s relationship develops quickly—as summer romances do—the depth of Carrie’s devastation sometimes feels disproportionate to what we’ve witnessed on the page. More scenes of genuine connection would strengthen the impact of later events.

Themes That Resonate

Lockhart wrestles with substantial questions throughout: What do we owe our families versus ourselves? How does privilege corrupt even well-intentioned people? Can we ever escape the patterns our parents establish? The novel suggests that lies, once told, metastasize—spreading through generations, poisoning relationships, destroying futures.

The examination of addiction deserves particular note. Carrie’s relationship with prescription pills never feels preachy or simplistic. Lockhart captures how substances promise relief from unbearable feelings while ultimately deepening isolation and self-destruction. The addiction storyline integrates seamlessly with themes of family expectations and unprocessed grief.

Comparisons and Context

Family of Liars will appeal to readers who loved:

- Karen M. McManus’s One of Us Is Lying for its mystery elements and privileged prep school dynamics

- Jandy Nelson’s I’ll Give You the Sun for its literary prose and complex sibling relationships

- Stephanie Perkins’s There’s Someone Inside Your House for Gothic atmosphere with contemporary settings

- Courtney Summers’s Sadie for its exploration of trauma and unreliable narration

- Madeleine Roux’s Asylum series for Gothic YA with psychological depth

Lockhart’s other works, particularly Genuine Fraud and Again Again, share this novel’s experimental structure and unreliable narrators. Her Ruby Oliver quartet offers a lighter introduction to her voice for readers intimidated by the darkness here.

The Verdict: A Worthy Addition to the Sinclair Saga

Family of Liars succeeds more often than it stumbles, delivering a prequel that deepens and darkens the original novel’s legacy. While it may not achieve the shocking perfection of We Were Liars, it stands as a compelling work in its own right—a Gothic examination of privilege, family, and the lies we tell ourselves to survive.

Lockhart’s greatest achievement here lies in making us sympathize with deeply flawed characters without excusing their actions. Carrie emerges as simultaneously victim and perpetrator, someone shaped by circumstances beyond her control who nonetheless makes choices with devastating consequences. This moral complexity elevates Family of Liars above typical YA fare.

The novel demands to be read thoughtfully, offering rewards for careful attention while delivering emotional gut-punches that linger long after the final page. It’s a book about beautiful people doing ugly things, about pristine beaches hiding dark secrets, about the way privilege protects those who least deserve protection.

Whether you’re returning to Beechwood Island or visiting for the first time, pack light. You’ll need room for all the emotional baggage this novel will give you to carry home.