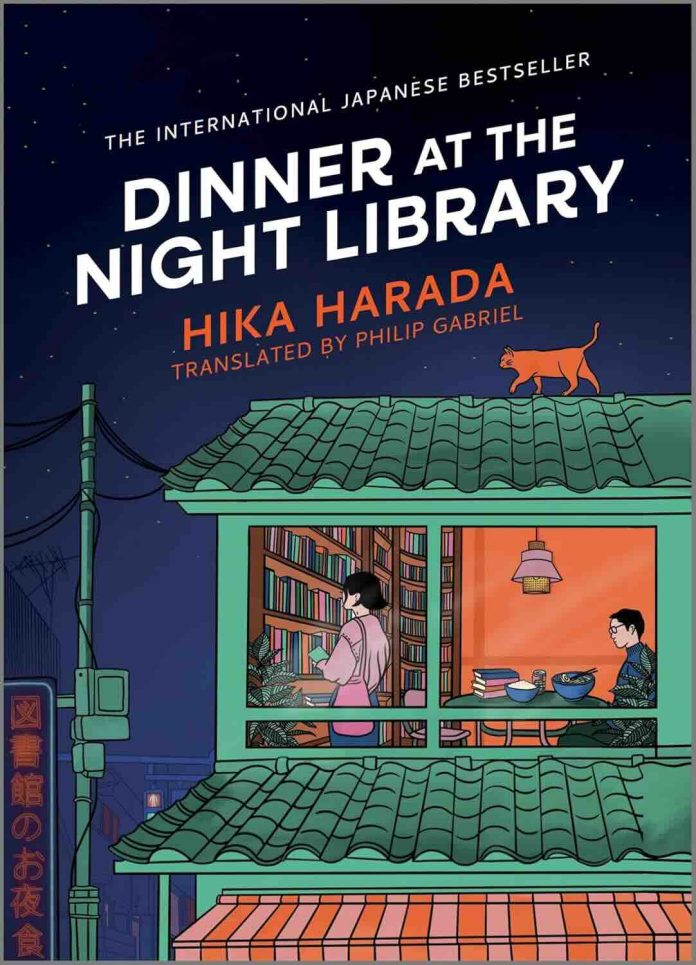

There exists a particular loneliness in loving books within an industry that no longer loves you back. Hika Harada’s Dinner at the Night Library, rendered into English by the capable hands of translator Philip Gabriel, understands this melancholy intimately. This slender novel, appearing almost as ephemeral as the institution it describes, offers readers something increasingly rare in contemporary fiction: a meditation on professional disillusionment wrapped in the gossamer of magical realism, where the extraordinary serves not to distract but to illuminate the achingly ordinary struggles of those who build their lives around literature.

The Architecture of Absence

Harada constructs her narrative around the Night Library, an establishment that operates under peculiar constraints. Open only from seven until midnight, housing exclusively works by deceased authors, permitting no loans—this is a library that functions more as memorial than lending institution. Into this carefully bounded world comes Otoha Higuchi, a young woman whose enthusiasm for books hasn’t yet been entirely extinguished by her previous experiences in the publishing world. Through Otoha’s perspective, we encounter a cast of bibliophiles who have each suffered their own professional wounds: editors whose authors abandoned them, booksellers whose shops succumbed to market forces, librarians displaced by budget cuts.

What distinguishes Harada’s approach is her refusal to sentimentalize these characters’ predicaments. The Night Library becomes not a refuge from reality but a crucible where damaged idealists must confront what their devotion to books has cost them. Each staff member carries a distinct narrative of compromise and loss, yet Harada resists the temptation to present them as martyrs to a noble cause. Instead, she observes them with clear-eyed compassion as they navigate the space between the careers they imagined and the circumstances they inhabit.

The Sustenance of Story

Central to the novel’s architecture is the ritual of shared meals, each dish inspired by literature housed within the library’s walls. These culinary interludes function as more than atmospheric detail; they become the mechanism through which colleagues transform into something resembling family. Harada writes these food scenes with specificity and care, understanding that the act of eating together represents a profound vulnerability. As the staff gathers around simple dishes—a stew mentioned in a forgotten novel, tea prepared according to a poet’s specifications—they gradually lower their defenses, revealing the disappointments and quiet desperations they’ve been carrying.

However, this narrative choice occasionally threatens to overwhelm the story’s momentum. The frequency of these meal scenes, while thematically resonant, can feel repetitive. By the novel’s midpoint, readers may find themselves wishing for greater variety in how these bonding moments manifest. The meals begin to blur together, each following a similar pattern of food preparation, consumption, and emotional revelation that, while moving initially, loses some impact through repetition.

Translation as Transformation

Philip Gabriel, renowned for his work on Haruki Murakami’s fiction, brings a measured sensitivity to Harada’s prose. The translation maintains the gentle, contemplative rhythm of the original while ensuring accessibility for English-language readers. Gabriel’s choices preserve the novel’s distinctly Japanese cultural context—the particular hierarchies of workplace relationships, the weight of obligation and duty, the subtle negotiations of personal space—without burdening the text with excessive explanation. The prose moves with a quietness that mirrors the library’s evening atmosphere, though occasionally this restraint tips into flatness, leaving readers wishing for more tonal variation.

Where Gabriel truly succeeds is in rendering the book’s central tension: the pull between individual desire and collective responsibility. This is territory he’s navigated in previous translations, and his experience shows in how naturally these cultural nuances emerge. The characters’ struggles feel both culturally specific and universally recognizable, a balance that requires considerable skill to achieve.

When Reality Fractures

The strange occurrences that begin infiltrating the Night Library represent the novel’s most ambitious reach. Books appear and disappear, whispers echo through empty aisles, time itself seems to behave oddly within these walls. Harada deploys these supernatural elements with admirable restraint, never allowing them to overtake the fundamentally human story she’s telling. Yet this restraint also prevents these elements from fully landing with the weight they might carry. The magical realism feels somewhat tentative, as if Harada isn’t entirely confident in pushing these boundaries.

This hesitancy creates a curious effect: the supernatural occurrences remain decorative rather than transformative. They enhance atmosphere without fundamentally challenging the characters or forcing them into genuine crisis. For a novel concerned with the question of what happens when everything you’ve built your life around proves unstable, there’s surprisingly little sense of genuine danger or upheaval. The threat of the library’s closure, which should serve as the narrative’s driving tension, never quite materializes as urgently as it might.

The Weight of Meaning

What Dinner at the Night Library does exceptionally well is capture the particular exhaustion of cultural workers in late capitalism. Otoha and her colleagues represent a generation raised to believe that passion justifies precarity, that loving what you do compensates for inadequate pay and uncertain futures. Harada doesn’t preach about these conditions; instead, she simply presents them, allowing readers to recognize the quiet toll they exact. The Night Library, with its mysterious anonymous owner and its impossible economics, becomes a fantasy not of escape but of impossible sustainability—a place where devotion to books might somehow be enough.

The novel’s conclusion, which I won’t spoil, asks its characters to reconsider their relationship with work and purpose. This is valuable territory, though Harada’s resolution feels somewhat too tidy, too reassuring for the complex questions she’s raised. The ending suggests possibilities without fully grappling with the structural forces that constrain those possibilities. It’s a hopeful conclusion that may leave some readers satisfied and others wishing for more complexity or challenge.

A Place in the Literary Landscape

For readers unfamiliar with Harada’s work, Dinner at the Night Library serves as an accessible introduction to her preoccupations with work, identity, and the sustaining power of small rituals. While this appears to be among her first novels widely available in English translation, her sensibility will feel familiar to readers of contemporary Japanese fiction that blends the mundane with the mysterious.

Those drawn to this novel might also consider Erin Morgenstern’s The Starless Sea, which similarly explores libraries as liminal spaces where reality bends, or Helen Oyeyemi’s Mr. Fox, which examines the relationship between creators and their creations. Closer to Harada’s cultural context, readers might explore Hiromi Kawakami’s Strange Weather in Tokyo for its quiet observation of loneliness and connection, or Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman for its examination of work and social conformity. Fans of Murakami’s more grounded fiction, particularly After Dark, will recognize the nocturnal Tokyo atmosphere and the sense of characters existing slightly outside normal time.

The Verdict from These Shelves

Dinner at the Night Library succeeds as a gentle, contemplative novel about finding community in unexpected places and questioning the narratives we’ve constructed around meaningful work. Harada writes with empathy and precision about people trying to maintain their idealism in an industry increasingly hostile to it. Her prose, skillfully translated by Gabriel, creates an atmosphere of hushed reverence appropriate to both libraries and late-night confidences.

Yet the novel’s strengths—its gentleness, its restraint, its careful observation—occasionally become limitations. The magical elements feel underdeveloped, the pacing sometimes lags, and the resolution arrives too neatly. These aren’t fatal flaws but rather indicate a novelist still finding the balance between the real and the fantastic, between observation and intervention. At approximately 200 pages, the book perhaps needed either more space to develop its supernatural elements or the courage to embrace a more purely realistic approach.

For readers seeking an immersive escape or a plot-driven adventure, this may not satisfy. But for those who understand the particular heartbreak of loving something that doesn’t love you back—whether that’s books, or a career, or the idea of what work should mean—Harada offers something valuable: recognition, rendered with care.

In the spirit of the Night Library’s commitment to transparency and honest exchange, I should note that this review of Dinner at the Night Library emerged from a copy provided by the publisher, who asked only that I offer my genuine response. Like the meals shared in Harada’s novel , this seemed a fair trade: sustenance offered, thoughts freely given in return. The book now sits on my shelf among others, waiting for whatever reader might need it next.