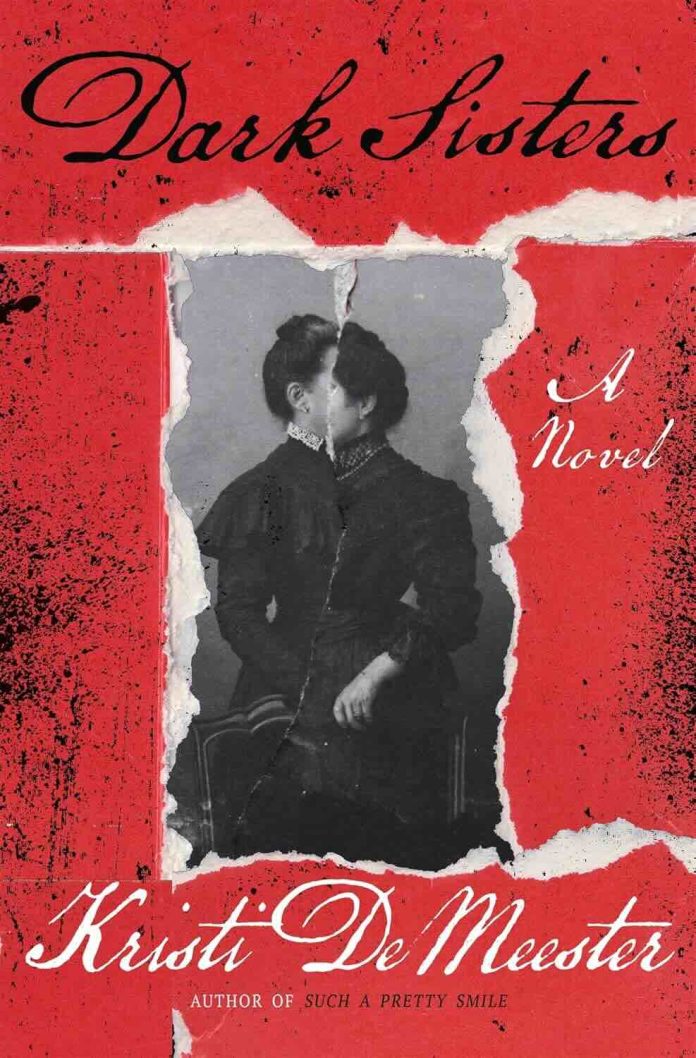

Kristi DeMeester’s Dark Sisters is a meticulously layered examination of feminine power, suppressed desire, and the terrible cost of denying one’s complete self. This multi-generational horror novel weaves together three narratives across three centuries—1750, 1953, and 2007—tracing the legacy of a curse born from betrayal and the women who must ultimately reclaim what was stolen from them. The novel operates as both Gothic horror and a searing critique of patriarchal religious structures that have historically weaponized women’s bodies and beliefs against them.

At its core, Dark Sisters follows Anne Bolton, a healer facing witchcraft accusations in colonial America; Mary Shephard, a 1950s housewife trapped in a suffocating marriage while conducting a forbidden affair with Sharon Hutchins; and Camilla Burson, a modern-day preacher’s daughter who defies her father’s oppressive church to uncover an ancient power connected to the Dark Sisters—spectral figures haunting the community of Hawthorne Springs. DeMeester’s narrative architecture is ambitious, and she largely succeeds in binding these disparate timelines through the central image of a black walnut tree that serves as both blessing and curse.

The Architecture of Dread

DeMeester demonstrates considerable skill in crafting atmosphere that feels suffocating yet beautiful. The prose itself mirrors the thematic concerns, moving between lush sensory details and stark, clinical descriptions of bodily horror. When describing the illness that plagues the women of Hawthorne Springs—bleeding gums, teeth falling like abandoned ornaments, flesh rotting from within—DeMeester never flinches. These aren’t metaphorical wounds; they’re visceral manifestations of betrayal, shame, and denial made corporeal.

The author’s previous works, including Such a Pretty Smile and Beneath, established her talent for excavating the horror lurking beneath suburban normalcy and feminine expectation. Dark Sisters represents a maturation of these themes, expanding her scope to encompass historical horror while maintaining the intimate, claustrophobic tension that defined her earlier fiction. Where Such a Pretty Smile focused on the monstrous transformation of adolescent girls under patriarchal pressure, Dark Sisters examines how entire lineages of women become infected by their own internalized shame and betrayal.

The structure alternates between the three timelines, with Anne’s 1750 narrative serving as interludes that gradually reveal the origins of the curse. This choice creates mounting tension as readers piece together the connections between past and present. However, the interweaving sometimes disrupts momentum, particularly in the middle sections where Mary’s 1953 storyline occasionally feels stalled by domestic detail. DeMeester’s commitment to authenticity in depicting Mary’s constrained existence as a housewife results in passages that, while thematically resonant, slow the narrative’s propulsive dread.

Forbidden Love and Bodily Autonomy

Mary and Sharon’s relationship forms the novel’s emotional heart. DeMeester writes their romance with aching tenderness, never sensationalizing their connection or reducing it to tragedy porn. The scenes between them pulse with genuine longing and the specific desperation of love that must hide itself. When Mary meets Sharon in Rich’s department store—a golden-haired shopgirl who tells Mary she “glows”—the attraction feels immediate and inevitable, rendered through small, perfect details: Sharon’s cool fingers brushing Mary’s neck, the way she holds a gilded mirror, the scarlet perfection of her painted mouth.

Yet DeMeester refuses to grant easy resolutions. Mary’s ultimate fate is brutal, her body becoming yet another offering to the community’s vampiric consumption of women’s vitality. The novel suggests that Mary’s illness springs not merely from a supernatural curse but from the impossibility of living authentically within Hawthorne Springs’ rigid structures. Her body literally betrays her because she cannot stop betraying herself—choosing domesticity over desire, husband over happiness, social acceptance over authentic love.

The Weight of Maternal Legacy

The relationship between Anne Bolton and her daughter Florence provides the novel’s most complex emotional terrain. Anne, a practitioner of natural magic, attempts to secure prosperity for her community through blood magic, only to have Florence—devout in her Christian faith and resentful of her mother’s heterodoxy—twist the blessing into a curse. Florence’s betrayal stems from genuine religious conviction mixed with filial anger, and DeMeester treats both motivations with nuance.

This mother-daughter dynamic echoes through the contemporary timeline with Camilla and her mother Ada. Ada, infected by the same wasting illness, cannot admit the truth of what she witnessed at her own Purity Ball—a ritualistic bloodletting disguised as religious ceremony. Her denial becomes its own curse, passed to Camilla, who must ultimately accept all parts of herself—light and dark, fury and love—to break the cycle.

Religious Horror and Bodily Violation

DeMeester’s depiction of The Path, Hawthorne Springs’ fundamentalist Christian community, is where the novel achieves its most trenchant social commentary. The Purity Ball—a ceremony where young girls pledge their virginity to their fathers—becomes the setting for secret violence. Church leaders, including Camilla’s father Pastor Burson and her ex-boyfriend Grant, drug the girls and drink their blood, believing it grants them prosperity and power. This vampiric consumption literalizes the ways patriarchal religious structures have always consumed women’s bodies and autonomy.

The horror here is twofold: the physical violation and the psychological manipulation that frames these violations as holy acts. Girls wake with scars they’re told came from fainting spells, their memories dismissed as dreams. The novel suggests that the real curse isn’t Florence’s angry plea for justice but the foundational violence of communities built on women’s subjugation.

However, the revelation of this conspiracy occasionally strains credibility. While thematically powerful, the mechanics of how church leaders maintain this blood-drinking ritual across generations—with wives, mothers, and entire families somehow complicit through denial—requires substantial suspension of disbelief. DeMeester works to address this through the supernatural compulsion of the curse, but the social dynamics still feel somewhat under-explored.

The Power of Acceptance

The novel’s central thesis—that women must accept the darkness within themselves alongside the light—represents both its greatest strength and occasional weakness. DeMeester argues convincingly that shame and denial create illness, that rejecting uncomfortable truths about ourselves becomes literally toxic. The women who survive are those who can hold contradictions: Anne’s daughter eventually recognizes both her love and resentment; Camilla embraces the witch label she once feared; the contemporary women of Hawthorne Springs acknowledge their own betrayals and complicity.

Yet this theme sometimes feels too neatly resolved in the climactic scene where Camilla summons all the women to the black walnut tree for reckoning. The men who stole their blood die, impaled on branches in an echo of historical violence, while the women are healed and empowered. This reversal—satisfying as wish fulfillment—doesn’t quite earn its catharsis given the novel’s previous commitment to showing how deeply women internalize oppression. The suggestion that simply accepting one’s darkness and anger can immediately cure generational trauma feels somewhat reductive after hundreds of pages demonstrating its complexity.

Gothic Craftsmanship

DeMeester’s prose shines in moments of Gothic excess. Descriptions of the black walnut tree—its bark holding faces that aren’t quite faces, its sap flowing like blood, its branches heavy with corpses—achieve genuine unnerving beauty. She has a gift for making natural imagery feel simultaneously sacred and obscene:

“The forest was silent. The birds paused in their song to observe the procession of women as it went. The trees were still, the wind unmoving. The moon rinsed all it touched in a pale glow. Each of the women marked by its light. Had there been crowns, they would have worn them like goddesses reborn in a world that had long forgotten them and the magic they carried.”

These moments of elevated language contrast effectively with the bodily horror, creating texture that keeps the novel from settling into a single register. Yet occasionally, the prose tips toward overwriting, particularly in the contemporary sections where Camilla’s interior monologues sometimes feel more literary than authentic to her character as a rebellious twenty-something.

Structural Ambitions and Minor Stumbles

The novel’s ambition is admirable but sometimes works against narrative cohesion. With three full storylines spanning 250+ years, DeMeester must compress character development and plot momentum. Mary’s romance with Sharon, while emotionally resonant, unfolds in fragments that don’t always accumulate into a fully realized arc. Similarly, Anne’s colonial narrative, relegated to brief interludes, feels rushed in its final movements when her understanding of the curse and attempt at reversal happen rapidly after slow buildup.

The contemporary timeline fares best structurally, benefiting from the novel’s present-tense immediacy and Camilla’s compelling voice. Her relationships—with best friend Brianna, loyal Noah, and the enigmatic Dark Sisters themselves—receive enough page time to feel earned. However, the Retreat facility where rebellious daughters are “reformed” could have been more fully rendered; it functions more as plot device than fully realized setting despite its thematic importance.

A Testament to Feminist Horror

Despite these quibbles, Dark Sisters succeeds as feminist horror that takes women’s rage, desire, and power seriously. DeMeester refuses to punish her female characters for their sexuality or their anger—indeed, the novel suggests these are sources of power rather than shame. The women who die are those who deny themselves, who betray their own knowledge and desire for social acceptance or safety.

This positions the novel within a contemporary wave of horror fiction interrogating gender violence and women’s subjugation, sharing thematic territory with works like Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties, Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Mexican Gothic, and Catriona Ward’s The Last House on Needless Street. Like these works, Dark Sisters uses genre conventions to examine how patriarchal structures literally make women sick, how internalized misogyny becomes a curse passed from mother to daughter, and how liberation requires accepting uncomfortable truths about ourselves and our communities.

Final Verdict

Dark Sisters is an ambitious, deeply felt examination of feminine power, bodily autonomy, and the terrible cost of denial. DeMeester’s prose moves between beautiful and brutal, her plotting ambitious if occasionally uneven. The novel works best when examining intimate relationships—Mary and Sharon’s doomed romance, Anne and Florence’s fraught mother-daughter bond, Camilla’s struggle against her father’s oppressive faith. It falters slightly in its structural complexity and in fully earning its climactic catharsis.

For readers seeking horror that grapples seriously with gender, sexuality, and religious oppression, Dark Sisters offers rich rewards. It demands engagement with difficult questions about complicity, betrayal, and the ways we inherit both power and trauma from our ancestors. The novel’s heart beats strongest in its insistence that women must claim all parts of themselves—the light and the dark, the pure and the profane—to break free from the curses that bind them.

- Recommended for readers who enjoyed: Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties, Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Mexican Gothic, Paul Tremblay’s A Head Full of Ghosts, Leïla Slimani’s Adèle, Sarah Waters’ Fingersmith, and for fans of folk horror examining religious communities and generational trauma.