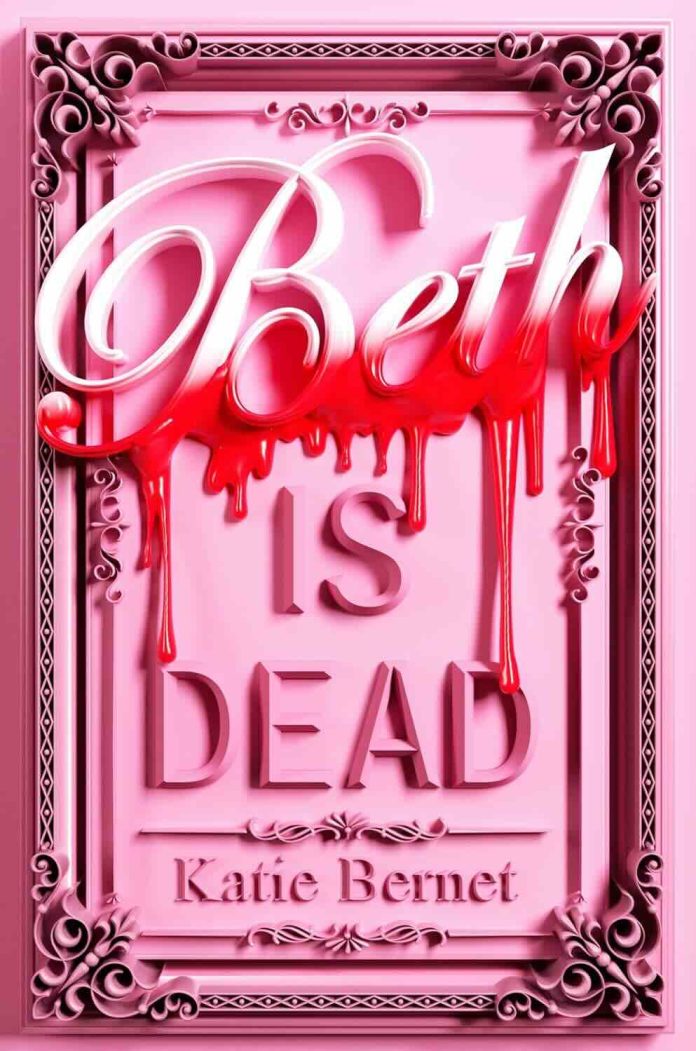

Contemporary fiction often borrows from classics, but Katie Bernet’s debut novel transforms Louisa May Alcott’s beloved sisterhood into something darker, more urgent, and devastatingly relevant. Beth Is Dead by Katie Bernet isn’t simply a retelling—it’s an interrogation of what happens when art collides with reality, when fame devours privacy, and when love becomes indistinguishable from obsession.

The premise strikes with immediate force: Beth March’s body discovered in winter woods on New Year’s Day, her sequined dress glittering against bloodstained snow. What unfolds isn’t just a murder mystery but an excavation of how we consume stories, how we exploit tragedy, and whether any narrative can truly capture the complexity of a life lived.

Where Fiction Bleeds into Reality

Beth Is Dead by Katie Bernet constructs its narrative foundation on a brilliantly meta concept: what if the March sisters existed in our world, and their father Rob March wrote a controversial bestseller called Little Women that exposed their private lives to public scrutiny? The novel opens with this uncomfortable reality already established—Beth has become the girl who “dies in the book,” subjected to morbid fascination, internet memes, and strangers who treat her mortality as entertainment.

Bernet’s execution of this premise demonstrates remarkable restraint. Rather than drowning readers in exposition, she reveals the family’s fractured relationship with fame through organic details: protesters outside their home, vandalized garages spray-painted with “KILLER,” recording devices planted beneath pianos. The March sisters navigate a world where their identities have been commodified, their private traumas transformed into bestseller fodder. When Beth actually dies, the line between Rob March’s fiction and his daughters’ reality collapses entirely.

The investigation structure propels the narrative forward with relentless momentum. Bernet employs alternating perspectives from Jo, Meg, and Amy—each sister processing grief through increasingly desperate attempts to solve the mystery themselves. Beth’s chapters arrive as flashbacks, creating a haunting counterpoint to the present-day investigation. These temporal shifts never feel disorienting; instead, they construct a portrait of Beth that the March patriarch’s book could never capture—the real, messy, imperfect girl behind the saintly character.

Sisters as Suspects, Love as Evidence

The genius of Beth Is Dead by Katie Bernet lies in how it systematically examines each sister as both investigator and potential suspect. Jo, the aspiring writer with hundreds of thousands of social media followers, once staged a break-in for attention—could she have escalated to murder for the ultimate story? Meg harbors secrets about academic fraud that could destroy her Harvard career. Amy’s drunken fight with Beth hours before her death plants seeds of devastating doubt.

Bernet navigates these suspicions with psychological acuity, capturing how grief warps perception and desperation breeds paranoia. The sisters’ relationships fray under investigation pressure, each accusation revealing deeper wounds: Jo’s resentment over being eclipsed by Amy’s relationship with Laurie, Meg’s exhaustion from playing family peacekeeper, Amy’s fury at being perpetually dismissed as immature. The mystery plot serves the character work rather than overwhelming it.

Detective Davis emerges as a fascinatingly flawed antagonist—not villainous but blinkered by experience and prejudice. His investigation of Jo feels simultaneously logical and unjust, highlighting how young women’s ambitions are pathologized while men’s are celebrated. When he dismisses the recording device incident as attention-seeking rather than investigating genuine threats, Bernet indicts a system that fails to protect the vulnerable while scrutinizing their reactions to trauma.

The revelation of Henry Hummel as Beth’s killer lands with tragic inevitability rather than shock. Bernet plants breadcrumbs throughout—his obsessive marginalia in Rob March’s books, his grandfather’s confused mentions of a Christmas Eve breakup, his desperate need to prevent Beth from leaving for Plumfield. The final confrontation at the family cabin crystallizes the novel’s meditation on possessive love: Henry loved Beth so intensely he couldn’t conceive of existing without her, making her murder both unintentional and inevitable.

Narrative Structure and Pacing

Bernet’s structural choices elevate what could have been a straightforward mystery into something more ambitious. The multiple perspectives never feel redundant because each sister’s voice carries distinct rhythms and preoccupations. Jo’s chapters crackle with defensive energy, her prose sharp and self-aware. Meg’s sections bleed with exhaustion and suppressed emotion. Amy’s perspective pulses with adolescent intensity—everything feels urgent, everything matters desperately.

Beth’s flashback chapters provide the novel’s emotional core, revealing a young woman struggling to define herself beyond others’ expectations. Her relationship with Henry initially appears tender—their shared love of video games, his gentle care for his grandfather—but Bernet gradually exposes darker undercurrents. The Christmas Eve breakup scene, revealed through fragmented memories, demonstrates Bernet’s skill at building dread through implication rather than graphic violence.

The pacing occasionally stumbles in the middle section when the sisters pursue multiple suspects—Fred Vaughn, Sallie Gardiner, John Brooke. These false leads, while narratively necessary, sometimes feel like padding rather than genuine investigation. However, Bernet redeems these detours by using them to deepen character relationships and expose family secrets that would otherwise remain hidden.

Themes of Exploitation and Authenticity

At its heart, Beth Is Dead by Katie Bernet interrogates how we consume and create stories about real people. Rob March’s Little Women represents artistic betrayal disguised as tribute—he exploited his daughters’ identities for literary acclaim, justifying the violation as love. The novel refuses easy condemnation of his actions while never excusing them, creating space for readers to grapple with uncomfortable questions about art’s relationship to life.

Jo’s parallel storyline as an aspiring writer compounds this thematic complexity. Her editor demands “more drama, more intrigue,” pushing her toward sensationalism over substance. When Jo begins writing about Beth’s murder, titling her manuscript Beth Is Dead, Bernet forces readers to confront our own complicity in consuming tragedy as entertainment. The novel we’re reading becomes uncomfortably aware of its own exploitation even as it critiques the practice.

Social media’s role in amplifying and distorting reality threads throughout the narrative. Jo’s follower count skyrocketed after the recording device incident—a violation that became valuable content. Beth endured strangers asking if she felt “dead inside” after her father’s book portrayed her death. Bernet captures the peculiar violence of digital age fame where private pain becomes public performance, where grief must be packaged for consumption.

Writing Style and Language

Bernet writes with sharp efficiency, favoring propulsive sentences over ornate prose. Her dialogue crackles with authenticity, capturing how actual teenagers speak—interrupted thoughts, half-finished sentences, emotional outbursts that arrive before filters engage. The March sisters’ arguments feel uncomfortably real, their love for each other expressed through criticism as often as support.

The novel’s treatment of violence deserves particular recognition. Bernet refuses to fetishize Beth’s death or provide graphic details that would satisfy prurient curiosity. The murder’s revelation arrives through Henry’s fragmentary confession, emphasizing psychological horror over physical gore. This restraint serves the story’s themes—Beth’s death isn’t entertainment, and Bernet won’t allow readers to consume it as such.

Occasional lapses into melodrama emerge during emotional confrontations, particularly in Amy’s chapters where teenage intensity sometimes tips into overwrought territory. However, these moments feel authentic to adolescent experience rather than authorial miscalculation. Amy would declare everything with capital-letter importance because everything is monumentally important when you’re sixteen and your sister is dead.

Critical Observations

While Beth Is Dead by Katie Bernet succeeds admirably in most respects, certain elements feel underdeveloped. The role of the March matriarch, Maggie, remains frustratingly peripheral despite her obvious importance to family dynamics. Her complicated marriage to Rob deserves deeper exploration, particularly her complicity in his decision to publish Little Women without daughters’ full consent.

The novel’s resolution rushes slightly, compressing Henry’s confession and the family’s processing of Beth’s death into the final chapters. After methodically building tension throughout, the denouement feels abbreviated. Jo’s decision to write a memoir celebrating Beth’s life rather than exploiting her death provides thematic closure, but the execution feels rushed compared to the careful pacing of earlier sections.

Detective Kirke’s character, while sympathetic, never fully escapes the “good cop” archetype. Her youth and empathy contrast effectively with Davis’s jaded cynicism, but Bernet could have complicated her further. The brief mentions of her being a new detective hint at interesting professional struggles that remain unexplored.

Comparative Context

Readers who appreciated Karen M. McManus’s One of Us Is Lying will recognize familiar territory in Beth Is Dead by Katie Bernet—the YA mystery structure, the multiple suspect misdirection, the exploration of teen social dynamics under extreme pressure. However, Bernet’s novel carries greater literary ambition, interrogating not just whodunit but whether solving mysteries about real people’s deaths can ever truly satisfy.

E. Lockhart’s We Were Liars shares Beth Is Dead by Katie Bernet‘s interest in privileged families harboring dark secrets, though Bernet’s approach feels grittier and more grounded in contemporary reality. The social media elements and cancel culture themes give this novel a specificity that will resonate with readers navigating similar digital landscapes.

For those seeking more literary retellings of classic texts, Kaitlyn Greenidge’s Libertie or Natasha Solomon’s Mr. Rosenblum Dreams in English demonstrate how contemporary authors can honor source material while transforming it into something entirely new—a feat Bernet accomplishes with confidence in her debut.

Similar Reads Worth Exploring

- One of Us Is Lying by Karen M. McManus – Multiple POV murder mystery in high school setting

- We Were Liars by E. Lockhart – Family secrets and tragedy with unreliable narration

- Sadie by Courtney Summers – Sisters, grief, and investigation with alternating timelines

- A Good Girl’s Guide to Murder by Holly Jackson – Amateur teen detective investigating cold case

- The Cheerleaders by Kara Thomas – Small town mystery exploring sisterhood and loss

In the spirit of transparency: Simon & Schuster provided this reading copy through their publishing program, a gesture that funded my late-night page-turning but couldn’t purchase my opinions—those remain stubbornly mine, forged through bleary-eyed reading sessions and multiple pots of coffee.

Final Verdict

Beth Is Dead by Katie Bernet announces a significant new voice in YA thriller fiction. While occasionally stumbling in its pacing and leaving certain character threads frustratingly incomplete, the novel succeeds in its ambitious project of interrogating how we tell stories about real people and what we lose when private lives become public narratives.

Bernet writes with confidence uncommon in debut novels, trusting readers to navigate complex themes without heavy-handed guidance. The mystery structure serves deeper questions about family, exploitation, and whether any narrative—no matter how carefully crafted—can capture the full complexity of a human life.

Beth March deserved better than dying in her father’s book. She deserved better than becoming a murder victim in her own life. In creating a novel that honors her complexity while acknowledging the impossibility of truly knowing anyone, Bernet offers readers something rarer than a well-plotted mystery: a meditation on why we tell stories about loss and whether those stories can ever be anything more than beautiful, necessary lies.